Pubmed 라는 사이트가 있습니다.

이곳은 의학관련 논문을 검색하고 자유롭게 열람할 수 있는 사이트로서, 전세계적으로 유명한 곳입니다.

국내의 의사들도 의학관련 이슈에 대한 근거를 검색할때 이 사이트를 많이 이용합니다.

MSM 관련해서 펍메드를 검색한 결과, 마침 최신자료가 올라와 있기에 공유해봅니다.

2017년 3월 자료이고.... 무엇보다도 195개의 논문을 레퍼런스 하여 만든 내용이라서 상당히 신뢰도가 있다고 생각합니다.

* 원문링크 : https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5372953/

아래는 구글번역 돌려서 퍼온 것입니다.

번역이 매끄럽진 못하지만 뭔소리 하는건지는 대충 이해될 것입니다.

더 확실한 이해를 위해서는 영문 원본도 같이 참고하세요.

--------------------------------------------------------------------

Methylsulfonylmethane : 새로운식이 보조제의 응용과 안전

Matthew Butawan , 1 Rodney L. Benjamin , 2 및 Richard J. Bloomer 1, *

추상

Methylsulfonylmethane (MSM)은 항염증제로서의 가장 보편적 인 사용을 포함하여 다양한 목적으로 사용되는 인기있는식이 보조제가되었습니다. 그것은 동물 모델뿐만 아니라 인간 임상 시험 및 실험에서도 잘 연구되어 왔습니다. 염증, 관절 / 근육통, 산화 스트레스 및 산화 방지제 용량을 포함한 MSM 보충제를 사용하면 다양한 건강 관련 결과 측정 방법이 개선됩니다. 최적의 이득을 제공하기 위해 필요한 정확한 투여 량과 시간 경과를 결정하기위한 추가적인 연구가 진행 중이지만, 이익을 제공하기 위해 필요한 MSM의 용량에 관한 초기 증거가있다. 일반적으로 인정 된 안전성 (GRAS) 승인 물질 인 MSM은 대부분의 개인이 매일 4 그램 이하의 용량으로 잘 견딜 수 있으며 알려진 부작용은 거의 없습니다.

키워드 : 메틸 술 포닐 메탄, MSM, 디메틸 술폰, 염증, 관절통

1. MSM의 설명 및 연혁

Methylsulfonylmethane (MSM)은 디메틸 술폰, 메틸 술폰, 술 포닐 비스 메탄, 유기 황 또는 결정 성 디메틸 술폭 시드 등 다양한 이름으로 보완 대체 의학 (CAM)으로 활용되는 자연 발생적 유기 황 화합물입니다 [ 1 ]. 임상 적용으로 사용되기 전에 MSM은 주로 모체 화합물 인 DMSO (dimethyl sulfoxide) [ 2] 와 마찬가지로 고온의 극성 비양 자성 상용 용매로 사용되었습니다.]. 1950 년대 중반까지 DMSO는 다른 약제의 공동 수송 여부, 항산화 능, 항염증제 효과, 항콜린 에스테라아제 활성 및 항 염증 효과를 비롯한 막 투과성을 비롯하여 독창적 인 생물학적 성질에 대해 광범위하게 연구되었습니다. 비만 세포로부터 히스타민 방출을 유도한다 [ 3 ]. 윌리엄스와 동료들은 후 4 , 5 ] 토끼 DMSO의 대사 연구, 다른 DMSO에 의한 생물학적 효과 중 일부는 부분적으로 그 대사 산물에 의해 야기 될 수 있다는 가정 (6) ].

1970 년대 후반, 크라운 Zellerbach 공사 화학자, 로버트 Herschler와 오레곤 건강의 박사 스탠리 제이콥과 과학 대학, DMSO [유사 치료 용도의 검색에있는 무취 MSM 실험을 시작했다 7 ]. 1981 년 박사 Herschler 손톱을 강화하기 위해, 매끄러운 피부를 부드럽게하는 MSM의 사용에 대한 미국 유틸리티 특허를 획득, 또는 한 혈액 희석제로 [ 8 ]. Herschler 특허는 MSM이 스트레스 해소, 통증 완화, 기생충 감염 치료, 에너지 증진, 신진 대사 촉진, 혈액 순환 증진 및 상처 치유 개선을위한 MSM을 주장했다. [ 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 , 13, 14 , 15 , 16 ], 과학적 근거는 거의 없다 [ 17 ]. 한편, 과학 문헌들은 MSM 관절염 [임상 응용 가질 수 있음을 시사 않는 18 , 19 , 20 와 같은 간질 성 방광염 [등] 등의 염증성 질환 (21) , 알레르기 성 비염 [ 22 , 23 ], 급성 운동성을 염증 [ 24 ].

MSM 조사 Herschler 한 MSM 제품 (OptiMSM의 특허 이후 확대되고 있지만 ® , 버그 스트롬 영양, 밴쿠버, WA, USA)를 일반적으로 2007 [식품 의약품 안전청에 의해 안전 (GRAS) 상태로 인식 수여되었다 25 ] MSM 이용 2012 [2002에서 크게 변하지 26 ]. 예를 들어, 1999-2004 년 국가 건강 및 영양 조사 (NHANES) 조사에 따르면 일반 MSM 사용자의 가중 백분율은 1.2 %입니다 [ 27 ]. 주관적인 설문 조사를 사용한 2007 년 연구에 따르면 설문 작성자 중 9.6 %가 MSM을 시도했다 [ 28]; 그러나 설문 조사를 완료 한 사람들의 표본은 다양하지 않았습니다. National Health Interview Surveys (NHIS)의 과거 데이터에 대한 더 최근의 분석은 2007 년과 2012 년 사이에 MSM 사용이 0.2 % 포인트 감소했다고 주장합니다 [ 26 ]. 최근 몇 년 동안 현재 MSM 판매 데이터를 기반으로 MSM 사용이 증가하고있는 것으로 나타났습니다.

1.1. MSM 합성 - 유황 사이클

MSM은 지구의 황주기 내 메틸 -S- 메탄 화합물 의 구성원입니다 . MSM의 자연적 합성은 조류, 식물 플랑크톤 및 다른 해양 미생물에 의한 디메틸 술 포니시 프로 피오 네이트 (dimethylsulfoniopropionate, DMSP) 생산을위한 황산염의 흡수로 시작된다 [ 29 ]. DMSP는 디메틸 설파이드 (DMS)를 형성하기 위해 분해되거나 메탄 티올을 생성하는 demethiolation을 거쳐 DMS로 전환 될 수있다 [ 30 ]. 대양에서 생산 된 DMS의 약 1 % -2 %가 에어로졸로 처리된다 [ 29 ].

대기 DMS는 오존, 자외선 조사, 질산염 (NO 3 ) 또는 수산기 라디칼 (OH)에 의해 산화되어 DMSO 또는 이산화황을 형성한다 [ 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 ]. DMSO 및 MSM의 대기 농도는 겨울 [에서 봄 / 여름 정재파와 계절에 의존 할 것으로 보인다 (36) , 가능 DMS 생산 및 변동성은 온도 종속되기 때문에. 이산화황과 같은 산화 된 DMS 제품은 응축과 구름 형성을 증가시킨다 [ 37 , 38, 따라서 DMS는 MSM 또는 [하나에 불균형을 겪을 수있는 침전을 용해 지구로 돌아 DMSO위한 수단을 제공한다 (39) ].

토양에 흡수되면, DMSO와 MSM 식물 [차지하는 것 40 ] 또는 예 bioremediative 첨가제로서 의존형 토양 박테리아에 의해 이용되는, 슈도모나스 푸티 다 (Pseudomonas putida) , 토양 조건 [개선하기 위해 41 , 42 , 43 , 44 , 45 , 46 ]. MSM은 많은 과일 [ 40 , 47 ], 채소 [ 40 , 47 , 48 ] 및 곡물 [ 47 , 49]], MSM 생물 축적 성의 정도는 식물에 따라 다르다. 이 시점에서 MSM과 다른 황원은 식물 생산물로 섭취되어 배설되며, 식물 호흡의 부산물로 유황 형태로 방출되거나 결국 식물이 죽으면 분해됩니다. 에어로졸이 공급되지 않은 황원은 황산염으로 산화되어 광물에 침투하여 침식되어 바다로 되돌아와이 황 서브 사이클을 완성합니다.

또는, 합성 적으로 생성 된 MSM은 DMSO를 과산화수소 (H 2 O 2 )로 산화 시키고 결정화 또는 증류로 정제함으로써 제조된다. 증류가보다 에너지 집약적 인 반면에, 바람직한 방법으로 인정되고 [ 50 ] GRAS OptiMSM ® (Bergstrom Nutrition, Vancouver, WA, USA) [ 25 ]의 제조에 활용됩니다. 생화학 적으로,이 제조 된 MSM은 자연적으로 생산 된 제품과 구조적 또는 안전성의 차이점을 발견 할 수 없다 [ 51].]. MSM의 농도가 식품 공급원의 100 분의 1에 있기 때문에, 합성 MSM은 비현실적인 양의 음식을 섭취하지 않고도 생체 활성 량을 섭취 할 수있게합니다.

1.2. 흡수 및 생체 이용률

MSM의 외인성 소스 [과일 등 식품의 섭취 또는 소비를 통해 체내로 도입된다 (40) , (47) ,] 야채 [ 40 , 47 , 48 , 입자 [ 47 , 49 ], 맥주 [ 47 ], 포트 와인 [ 52 ] 커피 [ 47 ], 차 [ 47 , 53 ], 젖소 [ 47 , 54 ]. MSM과 함께, 메티오닌, 메탄, DMS를 흡수하고, DMSO는 포유 동물 숙주 [내 MSM 집합체에 기여할 미생물에 의해 사용될 수있다 (55) , (56) , (57)]. 식이 유도 마이크로 바이 변경 래트 [혈청 MSM 레벨에 영향을 미치는 것으로 밝혀졌다 (58) ]와 gestating 암퇘지 [ 59 ]. 즉, 장내 식물은식이 요법 [ 61 ], 운동 [ 61 ] 또는 다른 요인에 의해 쉽게 조작되며 임신에서 제안 된 바와 같이 생체 이용 가능한 MSM 출처에 영향을 줄 가능성이 있습니다 [ 62 ].

약동학 연구에 따르면 MSM은 랫드 [ 63 , 64 ]와 인간 [ 65 ]에서 각각 2.1 시간과 1 시간 미만 으로 빠르게 흡수 된다. 원숭이에서 DMSO를 이용한 비슷한 연구는 경구 위관 영양법을 통한 전달 후 1-2 시간 이내에 DMSO가 MSM으로 빠르게 전환됨을 보여줍니다 [ 66 ]. DMSO 섭취 인간 NADPH의 존재 간 마이크로 솜에서 MSM 약 15 %의 산화 2 와 O 2 [ 56 ].

랫트에서 59 %와 79 %의 MSM 사이에서 변경 또는 다른 하나로서, 소변으로 투여 당일 배설 S 함유 대사 [ 64 ]. 소변은 MSM이 쥐 [ 63 , 67 ], 토끼 [ 4 , 5 ], 도살 고양이 [ 68 ], 치타 (cheetah) [ 69 ], 개 [ 70 ], 원숭이 [ 66 ] 등의 소변에서 가장 많이 발견되는 배설 형태입니다 . 및 인간 [ 4 , 62 , 71 , 72 ]. 또한 MSM의 배설은 대변에 포함될 수있다 [ 63 , 64] 또는 우유 [포함한 여러 다른 biofluids 54 , 73 , 드디어 꼬리 마개 분비 [ 74 ], 및 인간 타액 [ 75 ].

나머지 MSM은 상당히 균일 한 조직 분포와 쥐에서 약 12.2 시간의 생물학적 반감기를 나타낸다 [ 63 ]. 인간의 조직 분포는 뇌척수액에서 발견되고 뇌의 회색과 흰색 물질 사이에 균등하게 분포되어 있기 때문에 널리 확산 될 가능성이있다 [ 76 , 77 , 78 , 79 , 80 ]. 또한, 뇌 내의 생물학적 반감기는 7.5 시간 추정 [이다 (79) 일반 반감기보다 12 시간 [것으로 제시되지만,] 65 ]. 지속되는 전신 MSM은 생체 이용 가능한 원천으로 구성됩니다.

MSM은 유전학 [ 55 , 67 , 81 ] 및식이 [ 58 , 59 , 82 ]를 포함하되 이에 국한되지 않는 다양한 개인 특정 요인에 따라 정상 상태 농도가있는 일반적인 대사 산물입니다 . 1987 년 처음보고 된 기준 MSM 레벨은 700-1100 NG / ㎖ 또는 7.44-11.69 μmol / L [있었다 83 ]. 비슷한 결과가 0-25μmol / L의 낮은 마이크로 몰 범위의 수준에서 관찰되었다 [ 55 ]. 보다 최근에, 가능한 불일치는 13.3에서 103 μM / mL 범위의 기준선 MSM 수치를 나열하는 연구 보고서에 기록되어있다 [ 65]. 4 주 동안 건강한 남성 20 명당 3g으로 MSM을 매일 섭취하는 최근의 연구에서, 섭취 후 모든 남성에서 혈청 MSM이 증가했으며, 4 주째와 2 주째에는 추가로 증가한 것으로 나타났습니다. 대다수의 남성 [ 84 ]. 이 데이터는 경구 MSM이 건강한 성인에게 흡수되고 만성 섭취로 시간이 지남에 따라 축적된다는 것을 나타냅니다.

이동 :

2. 행동 메커니즘

멤브레인을 통과하여 체내로 침투하는 향상된 기능으로 인해 MSM의 완전한 기계적 기능은 세포 유형의 수집을 포함 할 수 있으므로 설명하기 어렵습니다. in vitro 및 in vivo 연구의 결과에 따르면 MSM은 염증 및 산화 스트레스의 교차 및 전사 수준에서 작용합니다. 이 유기 황 화합물의 크기가 작기 때문에 직접 효과와 간접 효과를 구별하는 것이 어렵습니다. 다음 섹션에서는 초점을 맞춘 범위 내에서 각 메커니즘을 설명하려고 시도합니다.

2.1. 항염증제

시험 관내 연구는 MSM 활성화 B 세포의 핵 인자 카파 경쇄 - 인핸서의 전사 활성 (NF-κB) 억제하는 것을 나타낸다 (85) , (86) 또한, NF-κB의 열화를 방지하면서 핵에 전위를 저해함으로써] 억제제 [ 86 ]. MSM은 세린 536 [에서 P65 서브 유닛의 인산화를 차단 포함 번역 후 변형 변화하는 것으로 나타났다 (87) 는이 직접 또는 간접적 인 효과인지 불분명하지만,]. 이와 같은 서브 유닛의 변형은 NF-κB의 전사 활성 조절에 크게 기여한다 [ 88]], 따라서이 항 염증 메커니즘을 더 이해하기 위해서는 더 많은 세부 사항이 필요합니다. 전통적으로, NF-κB 경로는 사이토 카인, 케모카인, 및 부착 분자 [코딩하는 유전자의 상향 조절을 담당하는 염증성 신호 전달 경로로 생각된다 (89) ]. (IL) -1, IL-6 및 종양 괴사 인자 α (TNF-α)를 인터루킨위한 mRNA를 하향 조절 NF-κB의 결과에 MSM의 억제 효과 시험 관내 [ 90 , 91 ]. 예상 한 바와 같이, 이들 사이토 카인의 번역 적 발현 또한 감소된다; 또한, IL-1, TNF-α는 용량 의존적으로 [에서 억제되고 90 ].

MSM은 또한 NF-κB의 억제를 통해 유도 성 산화 질소 합성 효소 (iNOS)와 cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2)의 발현을 감소시킬 수있다. 이와 같은 산화 질소 (NO)와 노이드 [으로 혈관 확장 성 제제의 생산을 줄이는 86 ]. NO 아니라 혈관 톤 [변조되지 92 ] 또한 비만 세포 활성화를 조절한다 [ 93 ]; 따라서 MSM은 간접적으로 염증의 비만 세포 매개 작용에 억제 작용을 가질 수 있습니다. 사이토 카인 및 혈관 확장 제의 감소로 국소 염증 부위로의 면역 세포의 유입 및 유입이 억제된다.

세포 내 수준에서, 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome을 함유 핵산 결합 도메인, 류신 - 풍부 반복 가족 pyrin 도메인은 세포 스트레스 신호를 감지하고, 염증 마커 [의 성숙에 은닉함으로써 응답 94 , 95 ]. MSM은 음 및 / 또는 미토콘드리아의 형태로 활성 산소 종 (ROS)에 활성화 신호를 생성 차단함으로써 NLRP3의 inflammasome을 사체의 NF-κB의 생산을 하향 조절함으로써 NLRP3의 inflammasome을 발현에 영향을 미친다 [ 90 ]. MSM이 항산화 특성을 나타내는 메커니즘은 다음 절에서 논의 될 것입니다.

2.2. 항산화 / 자유 라디칼 소거

ROS의 초과는 많은 세포 내 구성 요소에 혼란을 가져올 수 있지만, 표현형 적으로 정상 세포에서 적절한 경로를 활성화시키기 위해서는 역치가 필요하다 [ 96 ]. 호중구는 ROS의 생성은 시험관 내에서 억제하지만 무 세포 시스템에서의 영향을받지 않는 한 자극 때 MSM의 항산화 제 효과를 발견 하였다 [ 97 ]; 그러한 이유로, 항산화 메커니즘은 화학적 수준보다는 미토콘드리아에서 작용한다고 제안되었다.

MSM은 NF-κB, 전사 인자 (STAT), p53, 핵 인자 (erythroid-derived 2)와 같은 NF-κB, Nrf2와 같은 4 종 이상의 전사 인자의 활성화에 영향을 미친다. 이러한 전사 인자를 중재함으로써 MSM은 ROS와 항산화 효소의 균형을 조절할 수 있습니다. 이들 각각은 부분적으로 ROS에 의해 활성화된다는 점에 유의해야합니다.

이전에 언급했듯이, MSM은 NF-κB 전사 활성을 억제하여 ROS 생성에 관여하는 효소 및 사이토 카인의 발현을 감소시킬 수 있습니다. COX-2 및 iNOS의 하향 조절은 수퍼 옥사이드 라디칼 (O의 양을 줄여 2 - ) 및 산화 질소 (NO)는 각각 [ 86 ]. 또한, MSM은 TNF-α [카인의 발현을 억제한다 (86) , (90) , (91) 임의의 미토콘드리아 자극을 감소시킬 수있다], [ROS 생성 98 ]. 사이토 카인 발현의 감소는 감소 된 파라 크린 신호 전달 및 다른 전사 인자 및 경로의 활성화에도 관여 할 수있다.

MSM은 in vitro에서 많은 암 세포주에서 STAT 전사 인자의 발현이나 활성을 억제하는 것으로 밝혀졌다 [ 99 , 100 , 101 ]. janus kinase (Jak) / STAT 경로는 apoptosis, 분화 및 증식과 관련된 유전자의 조절에 관여하며, 이들 모두는 ROS를 필수 신호 성분으로 생성한다 [ 102 , 103 , 104 ]. Jak / STAT 경로를 통한 시그널링은 또한 감소 된 사이토 카인 발현에 의해 억압 될 수있다. JAK / STAT 경로를 하향 조절은 또한 산화 효소의 발현 [감소시켜 ROS의 생성을 감소시킬 수있다 (105) ] 및 B 세포 림프종 -2 (Bcl-2 단백질) [ 106 ].

대 식세포와 같은 세포에서의 시험 관내 MSM 사전 처리는 산화 환원 민감성 p53의 전사 인자의 축적을 감소시킬 것으로 밝혀졌다 (107) ]. 이 p53은 세포 내 ROS 수준에 따라 이분 산성 산화 기능을 나타내며, 일반적으로 p53은 낮은 ROS 수준의 세포 내 항산화 기능과 높은 ROS 수준의 prooxidative 기능을 발휘합니다 [ 108 ]. p53의 항산화 기능은 세스 트린 (Sestrin), 글루타티온 퍼 옥시다아제 (GPx) 및 알데히드 탈수소 효소 (ALDH)와 같은 소거 효소를 상향 조절합니다. p53의 prooxidative 기능은 항산화 물질을 억제하고 산화 물질을 억제합니다. p53과 산화 스트레스에 대한 심층적 인 요약은 Liu and Xu [ 108 ] 의 검토를 참조하십시오 .

인간 면역 결핍 바이러스 1 형 transactivating 조절 단백질 (HIV-1 Tat)으로 배양 한 쥐의 신경 모세포종 세포는 Nrf2의 감소 된 핵 전좌를 보였다. 그러나 MSM과 공동 배양하여 Nrf2를 핵으로 이동시켜 수준을 조절 하였다 [ 109 ]. Nrf2 잘 글루타메이트 시스테인 리가 (GCL), 수퍼 옥사이드 dismutases (SOD (항산화)), 카탈라제 (CAT), peroxiredoxin (Prdx) GPX, 글루타치온 S 트랜스퍼 라제 (GST) 등 [비롯한 항산화 효소와의 관계에 대해 설명하는 110 ] . 이 MSM은 Nrf2에 미치는 직접적인 어떤 영향 불분명하지만, Nrf2는 P21 또는 B 세포 림프종-초대형 BCL (-XL)의 JAK / STAT 발현 p53의 발현 [의해 조절 될 수 있다는 것을 언급 할 가치가있다 (111) ].

2.3. 면역 변조

스트레스는 병원체 인 경우 타고난 면역계에 의한 급성 반응과 적응 면역 반응을 유발할 수 있습니다. MSM을 포함한 유황 함유 화합물은 면역 반응을지지하는 데 중요한 역할을한다 [ 112 , 113 , 114 ]. 위에서 언급 한 것들을 포함한 통합 된 메커니즘을 통해, MSM은 산화 스트레스와 염증 사이의 크로스 토크를 통해 면역 반응을 조절합니다.

스트레스 요인에 만성적으로 노출되면 감작되거나 과도하게 스트레스를 받고 전형적인 면역 반응을 이끌어 낼 수 없기 때문에 면역계에 해로운 영향을 미칠 수 있습니다. IL-6의 확장 효과는 만성 염증 [의 유지에 관련되어있다 (115) ]. MSM은 시험 관내에서 IL-6를 감소시키는 것으로 밝혀졌으며 이로 인해 이러한 만성 해로운 영향을 완화시킬 수있다 [ 86 , 87 , 90 ]. LPS (lipopolysaccharide) 처리 된 혈액이 위약 그룹에서 관찰되지 않은 효과 인 생체 내 사이토 카인의 분비를 통해 여전히 반응을 나타낼 수 있기 때문에, 철저한 운동 전에 MSM으로 전처리함으로써 면역 세포의 과도한 스트레스를 예방했다 [ 24 ].

인접한 혈관계는 주로 비만 세포의 활성화를 통해 급성 면역 반응을 매개하는 역할을합니다. 비만 세포로부터의 히스타민 방출은 DMSO에 의해 억제된다 [ 116 ]. 그러나 MSM이 히스타민 방출에 미치는 영향은 아직 밝혀지지 않았습니다. 이전의 연구에 따르면 MSM은 혈관 기능을 억제하는 역할을합니다 [ 117 , 118 ]. 다른 in vitro 연구는 MSM이 NO 및 프로 스타 노이드와 같은 혈관 확장 제의 발현을 억제 할 수있는 능력을 가지고 있음을 보여줍니다 [ 86 ]. NO의 감소는 NO 대 식세포가 세포 사멸 [자극 보호 107 ].

또한, MSM은 세포주기 및 세포사와 관련된 다른 면역 조절 효과를 제공 할 수 있습니다. 시험 관내 연구는 MSM은 위장관 암 세포 [사멸을 유도 할 수 있음을 나타낸다 (119) , 간암 세포 [ 120 ], 및 대장 암 세포 [ 121 ]. 이러한 연구 결과는 달리, MSM은 쥐의 유방암 세포 [사멸을 유도하지 않았다 (122) ]. 오히려, MSM은 전이성 유방암 쥐 및 생쥐 흑색 종 세포 [모두 정상 세포 대사를 복원하기 위해 도시되었다 (123) ]. 세포주기 정지는 위장관 암 세포 [관찰되었다 (119) ]과 아세포 [ 124]. 이러한 세포 생존의 변화는 cyclin 생산 조절에서 p53 및 Jak / STAT 경로로 발생할 수 있습니다.

몇몇 연구는 상처 치유에 MSM의 효과를 조사 하였다 비록 체외 [의 긁힘 테스트에 의해 평가로, 선천성 면역 시스템은 또한, 강화 된 상처 봉합 혜택을 누릴 수있다 (124) , (125) , (126) ]. 미래의 연구는 생체 내에서 이러한 결과를 확인하는 데 필요합니다.

2.4. 유황 기증자 / 메틸화

MSM은 오랫동안 메티오닌, 시스테인, 호모 시스테인, 타우린 및 많은 다른 것들과 같은 유황 함유 화합물에 대한 유 도너로 생각되어 왔습니다. 기니 피그 메티오닌 및 시스테인 [함유 혈청 단백질로 방사성 표지 MSM 혼입 표지 황을 공급 (127) ]. 이 연구는 미생물 대사가 MSM을 이용하여 메티오닌을 형성하고이어서 시스테인으로 합성하는 원인이 될 수 있다고 제안했다. 방사성 표지 된 MSM에 대한보다 최근의 생체 내 연구는이 화합물이 균질 한 조직 분포에서 빠르게 대사되는 것을 제안한다 [ 63 , 64 ]. 이 연구는보고 된 바에 따르면 소변에서 MSM의 대사 산물로 대부분의 표지 황을 수집 하였지만 대사 산물은 확인하지 않았다. 황 기증자로서의 MSM의 활성에 관한 더 많은 연구가 진행 중이다.

In humans, no MSM dose-dependent trends are observed between individuals for plasma sulfate and homocysteine changes [65]. With microorganisms largely responsible for sulfur utilization throughout the sulfur cycle, MSM as a sulfur donor may be dependent on the existing microbiome with mammalian hosts.

MSM is reportedly a non-alkylating agent and does not methylate DNA [128]. In a letter by Kawai et al., the parent compound of MSM, DMSO, can methylate DNA in the presence of hydroxyl radical (OH) [129], which also has the potential to aid in the oxidation of DMSO to MSM [32,35]. Although it is uncertain whether MSM alkylates DNA, MSM does not appear to cause chromosome aberration in vitro or micronucleation in vivo according to two final study reports. Future studies are needed to determine whether MSM is a methyl donor.

3. 일반적인 용도

치료제로서 MSM은 독특한 침투성을 이용하여 세포 및 조직 수준에서 생리 효과를 변화시킵니다. 또한, MSM은 다른 치료제에 대한 담체 또는 공동 운반자로서의 역할을 수행 할 수 있으며, 잠재적 응용을 더욱 촉진시킬 수 있습니다.

3.1. 관절염과 염증

관절염은 현재 2,040 [의하여 78,400,000으로 추정 증가, 약 5800 만 성인 영향 관절의 염증 상태이다 (130) ]. 이 염증은 통증, 뻣뻣함 및 관절염 관절과 관련하여 감소 된 운동 범위로 특징 지어집니다. MSM은 현재 단독으로 CAM 치료를하고 있으며 관절염 및 기타 염증성 질환을 위해 병용합니다. 강화 된 침투성을 가진 미량 영양소 인 MSM은 일반적으로 글루코사민, 콘드로이친 황산염, 보스 웰릭 애시드 (boswellic acid)와 같은 다른 항 관절염 치료제와 통합됩니다.

이전에 언급했듯이 많은 시험 관내 연구 결과에 따르면 MSM은 사이토 카인 발현 감소를 통해 항 염증 효과를 나타냅니다 [ 86 , 87 , 90 , 91 ]. 실험 결과로 유도 된 관절염 동물 모델에서 MSM에서 유사한 결과가 관찰되었는데, 이는 마우스 [ 131 ] 및 토끼 [ 86 , 87 , 90 , 91 , 132 ]의 사이토 카인 감소에 의해 입증되었다 . 또한, 글루코사민 및 콘드로이틴 설페이트와의 조합 보충 MSM 효과적으로 실험적으로 유도 된 급성 및 만성 류마티스 관절염 [쥐에서 C 반응성 단백질 (CRP)을 감소 (133) ].

지금까지 관절염에 관한 대부분의 인체 연구는 비 침습적이었고 웨스턴 온타리오 및 맥 마스터 대학의 관절염 지수 (WOMAC), 36 품목 간략 조사 (SF36), 시각 아날로그 척도 (Visual Analogue Scale VAS) 통증 및 Lequesne 지수. MSM 자신의 개요 박사 스탠리 제이콥 MSM과 보완을 다음과 같은 개선 된 증상을 경험 관절염을 앓고있는 환자의 열한 사례 연구를 참조 [ 7 ]. 임상 시험은 VAS 통증 척도 [로 나타낸 바와 같이 MSM은 통증 감소 효과가 제안 18 , 134 ], WOMAC 통증 서브 스케일 [ 18 , 19 , 135 , 136 , SF36 통증 서브 스케일 [18 , 136 ], Lequesne Index [ 134 ] 등이있다. 동시 개선은 강성 [에서 언급 된 18 , 135 , 136 ] 및 [팽윤 134 ]. 또한, Usha와 Naidu [ 134 ]에 의해 수행 된 연구에서, 글루코사민과 함께 MSM은 통증, 통증 강도 및 붓기의 개선을 강화시켰다.

병용 요법을 이용한 다른 인체 연구에서도 비슷한 결과가보고됩니다. 예를 들어, 관절염과 관련된 통증과 뻣뻣함은 글루코사민, 콘드로이틴 설페이트, MSM (GCM) [ 137 , 138 ] 의 사용을 통해 상당히 개선되었습니다 . 골관절염으로 진단 된 정주 비만 여성 (OA) [ 139 ] 에서 GCM 조합을식이 요법 및 운동 수정 보완시 보았을 때 통증과 경직의 한계 개선 만이 관찰되었습니다 . boswellic 산 [함께 병용 MSM는 또한 관절염 통증을 감소 시키는데 효과적인 것으로 나타났다 (140) ] 및 II 형 콜라겐 [ 141 ].

관절염 외에도 MSM은 여러 다른 조건에서 염증을 개선합니다. 예를 들어, MSM은 유도 된 대장염 [생체 내 사이토 카인의 발현을 감쇠 (142) , 폐 손상 [ 143 ], 및 간 손상 [ 143 , 144 ]. 하세가와 (Hasegawa) [ 131 ]는 2.5 % 수성 수용액으로 전처리 한 후 국소적이고 급성 알레르기 성 염증을 가했을 때 MSM이 자외선 유도 염증으로부터 보호하는데 유용하다고보고했다.

MSM은 사람의 다른 염증성 병리학을 감소시키는 데에도 효과적입니다. 임상 사례 연구에 대한 의사의 검토에서, MSM은 간질 성 방광염을 앓고있는 6 명의 환자 중 4 명의 효과적인 치료법이었다 [ 21 ]. 또한 MSM은 계절성 알레르기 성 비염의 증상을 완화시키기 위해 제안되었다 [ 22 , 23 ]. MSM함으로써 전신 운동 유발 성 염증의 감소가 관찰 하였지만 [ 24 주어진 MSM [마우스에서 감소 활막염 염증에 도시 된 바와 같이, 인간의 연구는 연골 또는 활막 직접 염증 효과를 탐구되지 않은 145 ].

3.2. 연골 보존

연골 분해는 골관절염 길이 [의 구동력으로 간주되어 146 ]. 연골은 인접 활액 [에서 영양소 추출 구동없이 혈액 공급이 거의없이 치밀한 세포 외 기질 (ECM) 특징 (147) ]. 염증성 사이토 카인, 특히 IL-1β 및 TNF-α는 연골 ECM [의 파괴 과정에 연루되어있다 (148) ]. 최소한의 혈액 공급 가능한 저산소 미세 환경, 시험관 내 연구는 MSM은 IL-1β 및 TNF-α [에 미치는 억제 효과를 통해 연골을 보호 함을 제안한다 86 , 90 , 91 ] 및 세포 대사의 가능성 정규화 저산소증 구동 변경 [ 123 ] .

MSM에 의한이 파괴적인자가 분비 또는 파라 크린 신호 전달의 파괴는 OA 진행 동안 연골 및 활막 조직 [ 132 ], TNF-α 및 보호 관절 연골 표면 의 감소에 의해 외과 유도 OA 토끼에서 관찰되었다 . 증명 GCM이 조합 보충 류마티스 관절염 (RA) 래트 모델은 활막 조직 병리학 증식 및 관절 조인트 [에서 불규칙 에지의 개발 감소 133 ]. 또한, OA 생쥐 MSM 보충 크게 연골 표면 변성 [감소 (149) ]. 실제로 MSM의 보호 효과까지 거슬러 Murav'ev 및 동료 관절염 쥐의 무릎 관절 퇴행 감소 [바와 1991로 볼 수있다 (150)]. 흥미롭게도, 내인성 혈청 MSM은 양에서 증가된다 후 반월판 불안정화 골관절염 [야기 151 ]; 그러나,이 생리 반응의 크기는 연골 침식으로부터 보호하기에 충분히 크지 않았다.

3.3. 운동 범위 및 신체 기능 개선

앞서 언급 한 염증 및 연골 보존의 개선으로 주관적인 측정을 통해 전반적인 신체 기능의 놀라운 변화가 나타나지는 않았다 [ 18 , 19 , 135 , 136 ]. WOMAC [통해 평가로 매일 MSM 주어진 골관절염 인구 연구에서는 신체 기능에 상당한 개선이 관찰되었다 (18) , 19 , 135 , 136 , SF36 [ 19 , 135 , 136 , 집계 된 운동 기능 (ALF) 135]. 편심 운동에 의한 근육 손상을 다음과 같은 목적 운동 무릎 측정은 확정되지 않았다 그러나 MSM은 최대 등각 무릎 신근 복구 [에 도움이 될 수 있음을 시사 152 ].

MSM은 여러 가지 조합 요법에서 긍정적 인 결과로 사용되었습니다. 글루코사민, 콘드로이친 황산염, MSM, 구아바 잎 추출물, 비타민 D를 보충 한 결과, 일본 Knee OA Measure [ 137 ] 에 근거한 무릎 골관절염 환자의 신체 기능이 향상되었다 . GCM이 보충 기능 능력과 공동 이동성 [증가에 성공했다 (138) ]. boswellic acid와 함께 사용 된 MSM은 Lequesne Index [ 140 ]를 통해 평가 된 무릎 관절 기능을 향상시키는 것으로 나타났다 . MSM은 아르기닌과 l의 석 달 동안 촬영 -α-케 토글 루타 레이트, I 콜라겐 가수 분해를 입력하고, 브로 멜라 인 매일 포스트 회전근 수리 목적 기능적 결과 [영향을주지 않고 수리 무결성을 향상 153 ].

병용 요법에서 MSM의 사용을 모색하는 다른 연구들은 유의 한 개선을 보이지 않았다. 노인의 말에 하나 개의 연구에서는 GCM 조합 보충 3 개월 보행 특성 [중대한 변화 보여 실패 구두로 주어진 154 ]. 인간에서, MSM 및 boswellic 산은 소염제의 필요성을 감소하지만 gonarthrosis [치료제와 위약보다 효과적 아니었다 155 ]. 비 보충 기 [비교했을 때 다만, GCM 조합이 보충식이 및 운동 개입 외에 투여 한 경우, 유의 한 개선이 나타나지 않았다 (139) ].

요통은 MSM 글루코사민을 함유하는 복합체의 보급과 종래의 물리 치료를 받고 피사체 삶 [의 품질 개선보고 (156) ]. 척추 퇴행성 관절 질환 및 퇴행성 디스크 질환에 대한 치료로 GCM 보충제의 2011 체계적인 검토로 인해 품질 문헌 [의 부족에 효능에 대한 결론에 도달하는 데 실패했습니다 157 ].

3.4. 운동과 관련된 근육 통증을 줄이려면

장기간의 심한 운동은 근육 microtrauma 로컬 염증 반응 [선도 결합 조직 주위로 인한 근육통을 초래할 수 158 ]. MSM은 항 염증 효과뿐만 아니라 결합 조직에 유황이 기여할 수 있기 때문에 근육 통증에 대한 효과적인 약제로 언급됩니다. 크레아틴 키나아제 (creatine kinase) [ 159 ]에 의해 측정 된 MSM 보충으로 지구력 운동 유발 근육 손상이 감소되었다 . MSM을 사용한 전처리는 격렬한 저항 운동 [ 152 , 160 , 161 ]과 지구력 운동 [ 162 ]에 따른 근육 통증을 감소시켰다 .

3.5. 산화 스트레스 감소

시험 관내 연구는 MSM 화학적 자극 호중구 ROS를 중화하지 않는 것을 제안 대신 과산화물, 과산화수소, 차아 염소산 및 [미토콘드리아 생성 억제 97 ]. 또한, MSM은, 정상 수준으로 환원 글루타티온 (GSH) / 산화 글루타티온 (GSSG) 비 복원 NO 생산을 감소하지 않고, HIV-1 타트 노광 [다음 신경 ROS 생산을 감소시킬 수있다 (109) ]. 실험적으로 유발 된 손상에 대한 일차적 치료로서 MSM을 사용한 동물 연구는 말 론디 알데히드 (MDA) [ 142 , 143 , 144 , 163 , 164 , 165 ], GSSG [ 165 ], myeloperoxidase (MPO)142 , 143 , 163 , NO [ 164 ], 및 일산화탄소 (CO) [ 164 GSH [있음] 및 / 또는 증가 142 , 143 , 163 , 164 , 165 , 166 , CAT [ 142 , 143 , 144 , 165 ], SOD [ 143 , 144 , 163 , 165 ] 및 GPx [ 165 ]. 이러한 동물 연구에 대한 치료 방법은 예각 시간 량 또는 전처리 어느 종래 부상 [유도했다 (144) , (163), 165 ].

사람에서 지구력 운동 전에 MSM으로 전처리하면 유도 된 단백질 산화 [ 167 , 168 ], 빌리루빈 [ 159 , 168 ], 지질 과산화 [ 167 ], 크레아틴 키나제 [ 159 ], 산화 된 글루타티온 [ 167 ] 요산 (uric acid) [ 168 ] 그리고 총 항산화 제 용량의 증가 [ 159 , 168 ]. 지구력 운동에 이어 환원 글루타티온은 전처리 [10 일에 상승시키고 167 ] 미미하지만 [운동 바로 전에 하나의 경구 투여에 의해 영향을 받았다 (168) ].

저항 운동을받는 피험자에서 MSM으로 전처리하면 더 많은 변동성을 보입니다. 3.0 g / 일 전에 철저한 저항 운동에 28 일간 보충제 트롤 록스 동등한 항산화 제 용량의 증가 (TEAC) 및 호모시스테인 [감소 하였다 161 ]; 반면, 동일한 용량으로 14 일 동안 보충 TEAC 또는 호모시스테인 [에서 큰 변화가보고 (160) ]. 보충 기간이 길면 생체 이용 가능한 MSM 매장이 Nrf2를 상향 조절하여 항산화 효소를 더 많이 생산할 수있는 수준까지 도달 할 수있었습니다.

MSM을 포함한 복합 요법은 최근에 특히 MSM [ 169 ]에 의해 제공되는 투과성 증강으로 인해 EDTA (ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid)와 함께 보편화되었다 . 예를 들어, 국소 EDTA-MSM은 단백질 - 지질 알데하이드 부가 물의 형태로 산화 손상을 줄이는데 효과적이다 [ 170 , 171 , 172 ]. EDTA-MSM 당뇨병 성 백내장 [렌즈에서 혼탁 감소 172 ]하지만 쥐 [에서 실험적으로 유도 된 안압 역전에 효과적이었다 170 ]. 인간에서 EDTA-MSM 로션은 2 주간 투여 한 후 부종성 증상을 현저하게 개선 시켰으며 순환하는 총 항산화 용량과 MDA 감소가 나타났다 [ 173 ].

인간 연구는 MDA [ 19 , 167 , 168 ], 단백질 카르 보닐 (PC) [ 167 , 168 ], 요산 [ 168 ] 및 GSH [ 167 ]의 감소를 포함한 유사한 결과가 나타난 산화 방지제로서 MSM에 대한 약속을 보여준다 . TEAC [ 159 , 161 , 168 ]. 이전의 문헌과는 달리, Kantor et al. MSM 사용자가 60 분에 감소 된 림프구 DNA 복구 용량을 경험했다고보고했다. [ 174 ]. 이 상반되는 결과가 샘플에 의해 설명 될 수는 주기성 클록이 계수 [조절할 수 있기 때문에, 날에 다른 지점에서 수집 175 ].

3.6. 계절성 알레르기 개선

계절 알레르기에 대한 MSM의 평가에서, 30 일 동안 2.6g / 일 PO MSM은 3 주까지 호흡기 증상의 상부와 전체 호흡기 증상을 개선 시켰습니다 [ 23 ]. 이러한 모든 향상은 보충 30 일 동안 유지되었습니다. 이 연구의 단점은 꽃가루 수와 증상 설문에 대한보고가 부족하다는 점이다 [ 176 ]. Barrager와 Schauss가 요청 된 추가 데이터를 게시 할 때이 문제는 나중에 수정되었습니다 [ 22 ]. Barrager et al. 히스타민 방출을 측정이 샘플 모집단의 항을 사용하지만, 플라즈마 또는 IgE의 히스타민 수준 [에서 큰 변화가 발견 23 ].

3.7. 피부 품질과 질감 개선

1981 년 Herschler에게 수여 된 초기 특허 이후 MSM은 각질에 황 기증자로 작용하여 피부의 질과 질감을 향상시키는 치료 적 용도로 제안되었습니다. 마지막 연구 보고서에 따르면 MSM은 폐색 패치를 통해 토끼의 피부에 자극을주지 않는다고한다. 또 다른 마지막 연구 보고서는 MSM이 기니아 피그의 피부에 약간 자극적 일 수 있음을 나타냅니다. EDTA와 MSM을 포함하는 로션을 사용하여 쥐에 화상 부위에 경미한 개선은 매 8 시간 [국소 적용의 삼일 다음 발견되었다 (171) ].

MSM 치료 후 피부의 외관과 상태는 전문가의 평가, 도구 분석 및 참가자 자기 평가 [ 177 ]에 의해 평가 될 때 상당히 향상되었다 . 피루브산 및 MSM을 사용하여 네 박리 세션 인간의 조합 연구는 2 주에 1 회는 melisma, 피부 탄력의 착색의 정도 및 주름의 정도 [향상된 178 ]. MSM 실리마린과의 조합 치료는 주사 증상 [관리하는데 유용 179 ]. 심한 X 연계 형 어린 선을 가진 44 세 남자의 사례 연구는 아미노산, 비타민, 산화 방지제를 포함하는 국소 보습제 4 주 후 증상의 호전을 보였으며, MSM [ 180 ].

3.8. MSM 및 암

MSM 연구의 새로운 영역은 유기 황 화합물의 항암 효과를 다룬다. MSM을 단독 또는 조합하여 사용하는 시험 관내 연구는 유방암 ( 100 , 101 , 122 , 123 , 126 , 181 ), 식도암 ( 119 ), 위장관 암 ( 119 ), 간암 [ 119 , 120 ], 결장암 [ 121 ], 방광암 [ 99 ], 피부암 [ 123 , 125] 유망한 결과. MSM은 독립적으로 세포주기 정지 ( 119 , 122 , 123 ), 괴사 (necrosis) [ 119 ] 또는 세포 사멸 (apoptosis) [ 100 , 101 , 119 , 120 , 121 ] 의 유도를 통해 세포 생존을 억제함으로써 암 세포에 세포 독성을 보였다 . 세포 성장 및 증식의 억제는 전사 및 / 또는 번역 후 단계에서 MSM에 의해 유도 된 대사 변화에 기인 할 수있다. 예를 들어, MSM은 STAT3 [ 100 , 101 ] 및 STAT5b 와 같은 전사 인자의 발현 및 DNA 결합을 억제하는 것으로 나타났다 [ 100 ,101 , 181 ]; 한편, p53의 전사 인자는 MSM [의해 유지된다 (100) ] 및 아폽토시스 [유도하지 않는다 (121) ]. 비록 STAT3에 의한 DNA 결합의 MSM 저해가 Jak2의 인산화의 간접적 인 효과 일지 몰라도 [ 99 ]. 그럼에도 불구하고, 프로모터에 STAT3 및 STAT5b 결합하는 것을 억제함으로써, 혈관 내피 성장 인자 (VEGF)와 같은 발암 단백질의 발현이 감소 99 , 100 , 101 , 123 , 열 충격 단백질 (HSP) 90α [ 100 ], 및 인슐린 유사 성장 인자 -1 수용체 (IGF-1R) [ 99 , 100 , 101]가 관찰되었다. IGF-1R과 VEGF의 감소 된 발현은 인슐린 유사 성장 인자 -1 (IGF-1) 매개 세포 생존 및 증식 경로를 줄이고 종양 유도 성 혈관 신생을 예방함으로써 종양의 발생을 예방하는데 도움이 될 수있다 [ 182 , 183 ]. 이러한 대사 변화는 세포 수준에서도 심대한 변화를 일으킨다.

암 세포주에 대한 in vitro 연구는 MSM이 비 암세포와 더 유사한 표현형 변화를 자극 할 수있는 능력을 가지고 있음을 시사한다. 접촉 억제 및 세포 노화 [유도에서 MSM 결과로 처리 122 , 123 , 125 , 126 , 앵커리지 - 의존적 성장 [ 122 , 125 ], 전이 선 감소 이주 [ 101 , 122 , 125 , 126 , 정규화 상처 치유 [ 122 , 125 ]. 이것은 부분적으로는 미세 소관의 분해와 간접 재 조립을 포함하여 세포 필라멘트의 튼튼한 변화에 기인 할 수있다 [123 ], 액틴의 국소 재구성 [ 125 ]. 혈관 신생을 방지하기 저산소증 상태 메시지가 표시 될 수 있지만, MSM은 저산소 조건 [아래에서 HIF-1α의 레벨을 감소시키기 위해 도시 된 100 , 123 저산소증 [응답으로 다양한 전이성 생체]을 예방하거나 개선 123 ]. 체외 MSM 연구는 결과를 확인하는 추가 이종 이식과 생체 내 연구에 의해 뒷받침되었다.

암세포 MSM 처리 동물 모델로 xenotransplanted하는 경우 종양 성장 억제는 [관찰되었다 (99) , (100) , (101) 이 연구의 두 MSM 및 AG490 [조합 처리를 포함하지만,] 99 ] 또는 타목시펜 [ 101 ]. MSM 독점적으로 처리 된 마우스에서 종양 조직이 IGF-1, STAT3, STAT5b 및 VEGF의 현저한 억제없이 IGF-1R [발현 감소 나타내었다 (100) ]. 조합 치료 처리 이종 이식 된 마우스로부터 분리 된 조직 STAT5b 하향 조절을 표시하고 IGF-1R 신호 [모두 (99) , (101)]. 이전의 연구들은 또한 쥐에서 암을 유도하기 약 1 주 전 MSM으로 전처리하면 종양 발병까지의 평균 시간이 현저히 감소한다는 결론을 제시했다 [ 184 , 185 ]. 암 치료제 인 MSM을 이용한 인체 시험은 현재까지 수행되지 않았다. 그러나, 어느 연구는 MSM 사용이 폐 및 결장 직장암 [의 위험 감소와 연관 될 수 있음을 시사 186 ]. 시험 관내 및 생체 내 결과는 암에 대한 치료로서 MSM의 추가 조사를 보증합니다.

Go to:

4. 안전성

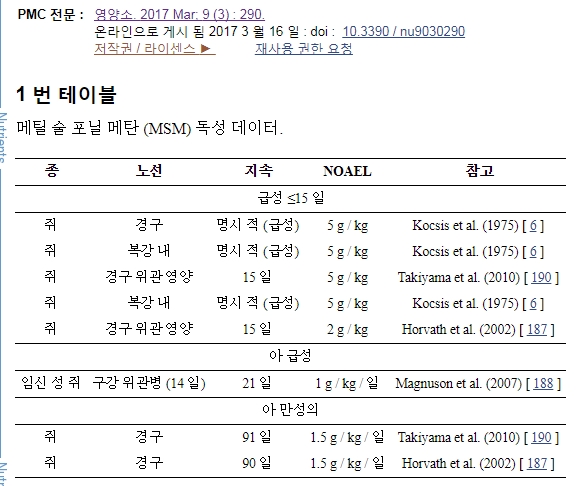

MSM은 내약 성이 뛰어나고 안전합니다. 여러 독성 연구가 쥐 [ 184 , 185 , 187 , 188 , 189 ], 마우스 [ 190 ], 개 [ 191 , 192]. 예비 독성 연구 보고서에서, 2 일 후에 15.4 g / kg의 경구 용 수성 투여 량을 투여 한 여성 쥐에게 단일 사망률이보고되었다. 그러나 사후 부검 검사에서 육안 적 병리학 적 변화는 보이지 않았다. 다른 기술 보고서에 의하면 MSM을 국소 적으로 도포했을 때 약한 피부와 눈의 자극이 관찰되었습니다. 그럼에도 불구하고 FDA (Food and Drug Administration) GRAS 통지에 따라 MSM은 4845.6 mg / day 이하의 용량으로 안전하다고 간주됩니다 [ 25 ]. 독성 연구 요약은 표 1에 열거되어있다 .

MSM 및 주류

만성 MSM 사용과 알코올에 대한 민감성 증가에 관한 웹 포럼 및 비디오의 많은 일화 적 증거가 존재합니다. 이러한 디 설피 다른 황 함유 분자, 알콜 [소모 때 부작용시킴으로써 알코올 중독을 방지하기 위해 사용되기 때문에 (193) ]는 알코올 대사 또는 중독 경로에 MSM 사용의 효과를 검사하는 현재까지의 연구는 없었다 언급 할 가치가있다. 이전에 언급했듯이, MSM은 혈액 뇌 장벽을 쉽게 가로 지르며 뇌 전체에 고르게 분포합니다 [ 76 , 77 , 78 , 79 , 80]; 그러나 연구는 다른 신경 경로에 대한 대사 효과에 초점을 두지 않았습니다. 레크리에이션 알코올 사용시 MSM 사용의 안전성을 평가하기위한 추가 연구가 필요합니다.

이동 :

5. 결론

MSM은 광범위한 생물학적 효과를 지닌 자연 발생적 유기 황 화합물입니다. 이 화합물의 인간 흡수와 생합성은 미생물과 숙주 사이의 공동 대사에 크게 의존한다. 자연적으로 생산 되었건 제조 된 것이 든, MSM은 산화 스트레스와 염증을 중재하는 능력에 생화학 적 차이를 보이지 않습니다. 이 미세 영양소는 관절염 및 염증, 신체 기능 및 성능과 관련된 여러 가지 조건에 잘 견딥니다. 새로운 연구에 따르면 MSM은 다양한 종류의 암 치료에 도움이 될 수 있습니다 [ 49 , 99 , 100 , 101 , 119 , 120 , 121 , 122 ,123 , 125 , 126 , 181 , 184 , 185 , 186 , 194 ] 또는 대사 증후군 [ 195 ].

이동 :

감사 인사

이 작품에 대한 기금은 멤피스 대학에서 제공했습니다.

이동 :

약어

ALDH 알데히드 탈수소 효소

ALF 집적 된 운동 기능

Bcl-2 B 세포 림프종 2

Bcl-XL B 세포 림프종 - 특대

BW 체중

캠 보완 대체 의학

고양이 카탈라아제

콜로라도 주 일산화탄소

콕스 사이클로 옥 시게나 제

CRP C- 반응성 단백질

DMS 디메틸 설파이드

DMSO 디메틸 술폭 시드

DMSP 디메틸 설폰 프로 피오 네이트

DNA 데 옥시 리보스 핵산

ECM 세포 외 매트릭스

EDTA 에틸렌 디아민 테트라 아세트산

GCL 글루타메이트 - 시스테인 리가 제

GCM 글루코사민, 콘드로이친 황산염, 메틸 술 포닐 메탄

GPx 글루타티온 퍼 옥시다아제

그라스 일반적으로 안전하다고 인정됨

GSH 감소 된 글루타티온

GSSG 산화 된 글루타티온

GST 글루타티온 S- 트랜스퍼 라제

H2O2 과산화수소

HIF-1α 저산소증 유도 성 인자 -1α

HIV-1 Tat 인간 면역 결핍 바이러스 1 형 불 활성화 단백질

HSP 열 충격 단백질

IGF-1 인슐린 유사 성장 인자 -1

IGF-1R 인슐린 유사 성장 인자 -1 수용체

IL 인터루킨

iNOS 유도 성 질산염 합성 효소

자크 야누스 키나 세

LD50 치사량

뇌 보호 시스템 리포 폴리 사카 라이드

MDA 말론 디 알데히드

MPO 미엘 퍼 옥시 다제

MSM 메틸 술 포닐 메탄

NADPH2 니코틴 아미드 - 아데닌 디 뉴클레오티드 인산염 감소

NF-κB 핵 인자 활성화 된 B 세포의 카파 - 경쇄 - 인핸서

NHANES 국민 건강 및 영양 조사

NHIS 국민 건강 인터뷰 조사

NLRP3 뉴클레오티드 - 결합 도메인, 3을 함유하는 류신 - 리치 반복 피린 도메인

아니 질산염

NO3 질산염

NOAEL 관찰 된 부작용 수준 없음

Nrf2 핵 인자 (적혈구 생성 2)와 유사한 2

O2 분자 산소

O2- 과산화수소 급진파

OA 기기 골관절염

오 히드 록실 라디칼

ppm 백만 분의 일

Prdx 과록 소 독소

로스 반응성 산소 종

SF36 36 품목 단 약형 설문 조사

잔디 과산화물 디스 뮤타 아제

STAT 트랜스 듀서의 신호 변환기 및 활성화 기

TEAC 트롤 록스 당량의 항산화 제 용량

TNF-α 종양 괴사 인자 - 알파

자외선 자외선

VAS 시각적 아날로그 스케일

VEGF 혈관 내피 세포 성장 인자

WOMAC 서쪽 온다 리오와 McMaster 대학 관절염 색인

이동 :

작성자 기고

MB, RJB 및 RLB는 원고의 작문 및 편집뿐만 아니라 문헌 검색에도 기여했습니다.

이동 :

이해 상충

MB는 공개 할 이해 관계가 없습니다. RLB는 Bergstrom Nutrition의 직원입니다. RJB는 MSM을 판매하는 사람들을 포함하여 건강 보조 식품 회사의 컨설턴트 및 연구비 지원을 받았습니다. 모든 저자는 최종 원고를 읽고 승인합니다.

이동 :

참고 문헌

1. Bertken R Crystalline dmso : DMSO 2 . 관절염 Rheum. 1983; 26 : 693-694. doi : 10.1002 / art.1780260525. [ PubMed ] [ 크로스 레퍼런스 ]

2. Clark T., Murray JS, Lane P., Politzer P. 왜 디메틸 술폭 사이드와 디메틸 술폰이 좋은 용매입니까? J. Mol. 모델. 2008; 14 : 689-697. doi : 10.1007 / s00894-008-0279-y. [ PubMed ] [ 크로스 레퍼런스 ]

3. Brayton CF Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) : 검토. 코넬 수의사. 1986; 76 : 61-90. [ PubMed ]

4. Williams KI, Burstein SH, Layne DS 토끼의 디메틸 설파이드, 디메틸 설폭 사이드 및 디메틸 설폰의 대사. 아치. Biochem. Biophys. 1966; 117 : 84-87. doi : 10.1016 / 0003-9861 (66) 90128-7. [ PubMed ] [ 크로스 레퍼런스 ]

5. Williams KI, Whittemore KS, Mellin TN, Layne DS 디메틸 술폭 시드를 토끼의 디메틸 술폰으로 산화. 과학. 1965; 149 : 203-204. doi : 10.1126 / science.149.3680.203. [ PubMed ] [ 크로스 레퍼런스 ]

6. Kocsis JJ, Harkaway S., Snyder R. 디메틸 술폭 사이드 대사 산물의 생물학적 영향. 앤. NY Acad. Sci. 1975; 243 : 104-109. doi : 10.1111 / j.1749-6632.1975.tb25349.x. [ PubMed ] [ 크로스 레퍼런스 ]

7. Jacob SW, Appleton J. Msm- 결정적인 안내서 : Methylsulfonylmethane의 과학 및 치료학에 관한 종합 검토. 자유 언론; Topanga, CA, USA : 2003.

8. Herschler RJ Methylsulfonylmethane 및 사용 방법. 4,296,130. 미국 특허. 1979 8 월 30 일;

9. Herschler RJ 동물의 식단을 향상시키기위한 메틸 술 포닐 메탄의 사용. 5,071,878. 미국 특허. 1991 Feb 6;

10. Herschler RJ는 고통을 경감시키고 고통과 야간 경련을 완화시키고 동물의 스트레스 유발 사망을 감소시키기 위해 메틸 술 포닐 메탄의 사용. 4,973,605. 미국 특허. 1989 7 월 26 일;

11. Herschler RJ 기생충 감염을 치료하기위한 메틸 술 포닐 메탄의 사용. 4,914,135 미국 특허. 1989 7 월 26 일;

12. Herschler RJ식이 제품 및 메틸 설 포닐 메탄을 포함하는 용도. 4,863,748. 미국 특허. 1986 년 6 월 26 일;

13. 식이 제품의 Herschler RJ Methylsulfonylmethane. 4,616,039. 미국 특허. 1985 Apr 29;

14. Herschler RJ MSM 및 그 생산물로 구성된 고형 의약품 조성. 4,568,547. 미국 특허. 1984 Feb 28;

15. Herschler RJ식이 및 의약 용 메틸 설 포닐 메탄 및이를 포함하는 조성물. 4,514,421. 미국 특허. 1982 9 월 14 일;

16. 메틸 술 포닐 메탄을 함유하는 허슬러 RJ 제제 및 사용 및 정제 방법. 4,477,469. 미국 특허. 1981 년 6 월 26 일;

17. Robb-Nicholson C. 그런데, 의사. msm은 들리는만큼 좋습니까? 식이 보충 교재에 대해 아무 것도 말해 줄 수 없습니까? 관절염 통증을 완화시켜야한다고 들었습니다. Harv. Womens Health Watch. 2002; 9 : 8. [ PubMed ]

18. Debbi EM, Agar G., Fichman G., Ziv YB, Kardosh R., Halperin N., Elbaz A., Beer Y., Debi R. 무릎 관절염에 메틸 술 포닐 메탄 보충제의 효능 : 무작위 통제 연구. BMC 보완. 대체. Med. 2011; 11 : 50 doi : 10.1186 / 1472-6882-11-50. [ PMC 무료 기사 ] [ PubMed ] [ Cross Ref ]

19. Kim LS, Axelrod LJ, Howard P., Buratovich N., Waters RF 무릎의 골관절염 통증에서 methylsulfonylmethane (MSM)의 효능 : 시험 임상 시험. 골격. Cartil. 2006; 14 : 286-294. doi : 10.1016 / j.joca.2005.10.003. [ PubMed ] [ 크로스 레퍼런스 ]

20. Lopez HL 골관절염 예방 및 치료를위한 영양 중재. 제 2 부 : 미량 영양소와 영양 보조 식품에 중점을 둡니다. PM R. 2012; 4 : S155-S168. doi : 10.1016 / j.pmrj.2012.02.023. [ PubMed ] [ 크로스 레퍼런스 ]

21. 간질 성 방광염의 치료에서 Childs SJ Dimethyl sulfone (DMSO 2 ). 우롤. 클린. N. Am. 1994; 21 : 85-88. [ PubMed ]

22. Barrager E., Schauss AG 계절 알레르기 비염의 치료제 인 Methylsulfonylmethane : 꽃가루 수와 증상 설문지에 대한 추가 데이터. J. Altern. 보어. Med. 2003; 9 : 15-16. doi : 10.1089 / 107555303321222874. [ PubMed ] [ 크로스 레퍼런스 ]

23. Barrager E., Veltmann JRJ, Schauss AG, Schiller RN 계절 알레르기 비염의 치료에서 methylsulfonylmethane의 안전성과 효능에 대한 다기능의 공개 상표 재판. J. Altern. 보어. Med. 2002; 8 : 167-173. doi : 10.1089 / 107555302317371451. [ PubMed ] [ 크로스 레퍼런스 ]

24. Van der Merwe M., Bloomer RJ 격렬한 운동 전후의 염증 관련 사이토 카인 방출에 메틸 술 포닐 메탄이 미치는 영향. J. Sports Med. 2016; 2016 : 7498359 doi : 10.1155 / 2016 / 7498359. [ PMC 무료 기사 ] [ PubMed ] [ Cross Ref ]

25. Borzelleca JF, Sipes IG, 식품 성분으로서 Optimsm (Methylsulfonylmethane; MSM)의 안전성 (GRAS) 상태를지지하는 Wallace KB 서류. 식품 의약청; Vero Beach, FL, USA : 2007.

26. Clarke TC, Black LI, Stussman BJ, Barnes PM, Nahin RL 성인 간 보완 적 건강 접근법의 추세 : 미국, 2002-2012. Natl. 건강 통계. Rep 2015; 79 : 1-16.

27. Kantor ED, Lampe JW, Vaughan TL, Peters U., Rehm CD, White E. 특수식이 보충제 사용과 c- 반응성 단백질 농도의 연관성. 오전. J. Epidemiol. 2012; 176 : 1002-1013. doi : 10.1093 / aje / kws186. [ PMC 무료 기사 ] [ PubMed ] [ Cross Ref ]

28. Wall GC, Krypel LL, Miller MJ, Rees DM fibromyalgia 증후군 환자에서 보완 대체 의학 사용에 대한 예비 연구. Pharm. 실천. 2007; 5 : 185-190. doi : 10.4321 / S1886-36552007000400008. [ PMC 무료 기사 ] [ PubMed ] [ Cross Ref ]

29. Sievert SM, Kiene RP, Schultz-Vogt HN 해양학. Vol. 20. 해양학 학회; Rockville, MD, USA : 2007. 유황 순환; pp. 117-123.

30. Bentley R., Chasteen TG 환경 voscs - 디메틸 설파이드, 메탄 티올 및 관련 물질의 생성 및 분해. 분위기. 2004; 55 : 291-317. doi : 10.1016 / j.chemosphere.2003.12.017. [ PubMed ] [ 크로스 레퍼런스 ]

31. Boucher O., Moulin C., Belviso S., Aumont O., Bopp L., Cosme E., Kuhlmann RV, Lawrence MG, Pham M., Reddy MS Dms 대기 농도 및 황산염 에어러솔 간접 복사 강제력 : 감도 dms 소스 표현과 산화에 대해 연구하십시오. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2003; 3 : 49-65. doi : 10.5194 / acp-3-49-2003. [ Cross Ref ]

32. Jorgensen S., Kjaergaard HG dms 및 그 산화 생성물에서 수소에 의한 수소 추출 반응에 수화가 미치는 영향. J. Phys. Chem. A. 2010; 114 : 4857-4863. doi : 10.1021 / jp910202n. [ PubMed ] [ 크로스 레퍼런스 ]

33. Kastner JR, Buquoi Q., Ganagavaram R., Das KC 목재 플라이 애시를 이용한 가스 환원 황 화합물의 촉매 오존 처리. 환경. Sci. Technol. 2005; 39 : 1835-1842. doi : 10.1021 / es0499492. [ PubMed ] [ 크로스 레퍼런스 ]

34. Qiao L., Chen J., Yang X. 냄새가 나는 디메틸 황화물의 UV에 의한 분해로 인한 잠재적 인 미립자 오염. J. Environ. Sci. 2011; 23 : 51-59. doi : 10.1016 / S1001-0742 (10) 60372-5. [ PubMed ] [ 크로스 레퍼런스 ]

35. Ramírez-Anguita JM, González-Lafont., Lluch JM 오 - 시작 dms 산화의 추가 채널에서 DMSO 2 의 형성 경로 : 이론적 연구. J. Comput. Chem. 2009; 30 : 1477-1489. doi : 10.1002 / jcc.21168. [ PubMed ] [ 크로스 레퍼런스 ]

36. Watts SF, Watson A., Brimblecombe P. 영국 섬의 해양 대기에서 메탄 설 폰산, 디메틸 설폭 사이드 및 디메틸 설폰의 에어로졸 농도를 측정. Atmos. 환경. (1967-1989) 1987; 21 : 2667-2672. doi : 10.1016 / 0004-6981 (87) 90198-3. [ Cross Ref ]

37. Charlson RJ, Lovelock JE, Andreae MO, Warren SG 해양성 식물성 플랑크톤, 대기 유황, 구름 알베도 및 기후. 자연. 1987; 326 : 655-661. doi : 10.1038 / 326655a0. [ Cross Ref ]

38. Lee PA, de Mora SJ, Levasseur M. 수중 환경에서 디메틸 설폭 시드에 대한 검토. Atmos.-Ocean. 1999; 37 : 439-456. doi : 10.1080 / 07055900.1999.9649635. [ Cross Ref ]

39. Harvey GR, Lang RF 해양 환경에서 Dimethylsulfoxide와 dimethylsulfone. Geophys. Res. 레트 사람. 1986; 13 : 49-51. doi : 10.1029 / GL013i001p00049. [ Cross Ref ]

40. Smale BC, Lasater NJ, Hunter BT 농작물에 함유 된 디메틸 술폭 사이드의 운명과 대사. 앤. NY Acad. Sci. 1975; 243 : 228-236. doi : 10.1111 / j.1749-6632.1975.tb25360.x. [ PubMed ] [ 크로스 레퍼런스 ]

41. Endoh T., H. Habe, 노 지리 H., 야마 네 H., T. 오모리 디메틸 술폰 활용도를 담당하는 슈도모나스 푸티 다 sfnfg 오페론의 발현을 조절 sfnr sigma54 종속 전사 활성. Mol. Microbiol. 2005; 55 : 897-911. doi : 10.1111 / j.1365-2958.2004.04431.x. [ PubMed ] [ 크로스 레퍼런스 ]

42. Endoh T., Habe H., Yoshida T., Nojiri H., Omori T. cysb 조절 및 sigma54 의존 조절 인자 sfnr은 pseudomonas putida strain ds1의 디메틸 술폰 대사에 필수적이다. 미생물학. 2003; 149 : 991-1000. doi : 10.1099 / mic.0.26031-0. [ PubMed ] [ 크로스 레퍼런스 ]

43. Endoh T., Kasuga K., Horinouchi M., Yoshida T., Habe H., Nojiri H., Omori T. pseudomonas putida strain ds1에서 디메틸 설파이드 이용에 필수적인 유전자의 특성 및 동정. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2003; 62 : 83-91. doi : 10.1007 / s00253-003-1233-7. [ PubMed ] [ 크로스 레퍼런스 ]

44. Habe H., Kouzuma A., Endoh T., Omori T., Yamane H., Nojiri H. 시그마 54 의존성 슈도모나스 푸티 다에 의한 황산 기아 유도 유전자 sfna의 전사 조절. 미생물학. 2007; 153 : 3091-3098. doi : 10.1099 / mic.0.2007 / 008151-0. [ PubMed ] [ 크로스 레퍼런스 ]

45. Kouzuma A., Endoh T., 오모리 T., H. 노 지리, 야마 네 H., H. Habe는 PTS 패밀리 단백질 EI (NTR)을 코딩하는 유전자는 PTSP 슈도모나스 푸티 다 (Pseudomonas putida)에 의한 디메틸 술폰 활용을 위해 필수적이다. FEMS Microbiol. 레트 사람. 2007; 275 : 175-181. doi : 10.1111 / j.1574-6968.2007.00882.x. [ PubMed ] [ 크로스 레퍼런스 ]

46. Kouzuma A., Endoh T., Omori T., Nojiri H., Yamane H., Habe H. 전사 인자 cysb와 sfnr은 pseudomonas putida에서 황산염 기아 반응에 대한 계층 적 조절 시스템을 구성한다. J. Bacteriol. 2008; 190 : 4521-4531. doi : 10.1128 / JB.00217-08. [ PMC 무료 기사 ] [ PubMed ] [ Cross Ref ]

47. Pearson TW, Dawson HJ, Lackey HB 선택된 과일, 채소, 곡류 및 음료에서 자연적으로 발생하는 디메틸 술폭 시드 수준. J. Agric. 식품 화학. 1981; 29 : 1089-1091. doi : 10.1021 / jf00107a049. [ PubMed ] [ 크로스 레퍼런스 ]

48. 양육을위한 biomarker로서 디메틸 술폰을 밝히고있는 탐구적인 nmr nutri-metabonomic 연구는 H., Roldan-Marin E., Dragsted LO, Viereck N., Poulsen M., Sanchez-Moreno C., Cano MP, Engelsen SB 섭취. 분석자. 2009; 134 : 2344-2351. doi : 10.1039 / b918259d. [ PubMed ] [ 크로스 레퍼런스 ]

49. Moazzami AA, Zhang JX, Kamal-Eldin A., Aman P., Hallmans G., Johansson JE, Andersson SO 핵 자기 공명 기반 대사 체는 전체 곡물 호밀 및 호밀 밀기울식이가 대사에 미치는 영향을 감지 할 수 있습니다 전립선 암 환자의 혈장 프로파일 J. Nutr. 2011; 141 : 2126-2132. doi : 10.3945 / jn.111.148239. [ PubMed ] [ 크로스 레퍼런스 ]

50. Bennet RC, Corder WC, Finn RK 기타 분리 공정. 있음 : Perry RH, Chilton CH, 편집자. 화학 공학자 안내서. 제 5 권 McGraw-Hill Book Company; 뉴욕, 뉴욕, 미국 : 1973.

51. FIRN R. 자연의 화학 물질 : 우리의 세계를 형성 한 천연물. 옥스포드 대학 출판물 수요; 옥스포드, 영국 : 2010. 4 장 : 천연물은 합성 화학 물질과 다른가요?

52. Silva Ferreira AC, Rodrigues P., Hogg T., Guedes de Pinho P. 포트 와인에서 디메틸 설파이드, 2-mercaptoethanol, methionol 및 dimethyl sulfone의 형성에 대한 기술적 매개 변수의 영향. J. Agric. 식품 화학. 2003; 51 : 727-732. doi : 10.1021 / jf025934g. [ PubMed ] [ 크로스 레퍼런스 ]

53. Kawakami M., Yamanishi T. 배전 또는 팬 - 발화 처리에 의한 팬 - 녹차 중 아로마 성분의 형성. Nippon Nogeikagaku Kaishi. 1999; 73 : 893-906. doi : 10.1271 / nogeikagaku1924.73.893. [ Cross Ref ]

54. Williams KI, Burstein SH, Layne DS 디메틸 술폰 : 젖소에서 분리. Proc. Soc. 특급. Biol. Med. 1966; 122 : 865-866. doi : 10.3181 / 00379727-122-31272. [ PubMed ] [ 크로스 레퍼런스 ]

55. Engelke UF, Tangerman A., Willemsen MA, Moskau D., Loss S., Mudd SH, Wevers RA 인간의 뇌척수액과 혈장의 Dimethyl sulfone이 일차원 1 H와 2 차원 1 H- 13 C에 의해 확인 됨. NMR. NMR Biomed. 2005; 18 : 331-336. doi : 10.1002 / nbm.966. [ PubMed ] [ 크로스 레퍼런스 ]

56. Gerhards E., Gibian H. 사람과 동물에서 디메틸 술폭 시드의 대사와 대사 작용. 앤. NY Acad. Sci. 1967; 141 : 65-76. doi : 10.1111 / j.1749-6632.1967.tb34867.x. [ PubMed ] [ 크로스 레퍼런스 ]

57. He X., Slupsky CM 미생물 - 포유 동물의 공동 대사에서 디메틸 술폰 (DMSO 2 ) 의 신진 대사 지문 . J. Proteome Res. 2014; 13 : 5281-5292. doi : 10.1021 / pr500629t. [ PubMed ] [ 크로스 레퍼런스 ]

58. Palmnäs MS, 코완 TE, Bomhof MR, 스와 J., 라이머 RA, 보글 HJ, Hittel DS, 시어러 J. 저용량 아스파탐 소비 차등식이 유도 비만 래트에서 장내 미생물 숙주 대사 작용에 영향을 미친다. PLoS ONE. 2014; 9 : e109841 doi : 10.1371 / journal.pone.0109841. [ PMC 무료 기사 ] [ PubMed ] [ Cross Ref ]

59. Yde CC, Bertram HC, Theil PK, Knudsen KEB 임신 한 암 in지의 혈장 대사 산물에 대한 식물성 및 농산물 부산물로부터 제조 된 고식이 섬유 다이어트의 효과. 아치. 애님. Nutr. 2011; 65 : 460-476. doi : 10.1080 / 1745039X.2011.621284. [ PubMed ] [ 크로스 레퍼런스 ]

60. 심슨 H., 캠벨 B. 리뷰 기사 :식이 섬유 - 미생물 상호 작용. 음식물. Pharmacol. 테러. 2015; 42 : 158-179. doi : 10.1111 / apt.13248. [ PMC 무료 기사 ] [ PubMed ] [ Cross Ref ]

61. Cerdá B., Pérez M., Pérez-Santiago JD, Tornero-Aguilera JF, González-Soltero R., Larrosa M. Gut microbiota modification : 신체 운동의 건강에 대한 퍼즐의 또 다른 부분은 무엇입니까? 앞. Physiol. 2016; 7 : 1-11. doi : 10.3389 / fphys.2016.00051. [ PMC 무료 기사 ] [ PubMed ] [ Cross Ref ]

62. Pinto J., Barros ANS, Domingues MRRM, Goodfellow BJ, Galhano EL, Pita C., Almeida MDC, Carreira IM, Gil AM 플라즈마의 nmr 대사 작용과 소변과의 상관 관계에 의한 건강한 임신 이후. J. Proteome Res. 2015; 14 : 1263-1274. doi : 10.1021 / pr5011982. [ PubMed ] [ 크로스 레퍼런스 ]

63. Magnuson BA, Appleton J., Ames GB 쥐에게 경구 투여 한 후 35S 메틸 술 포닐 메탄의 약물 동력학 및 분포. J. Agric. 식품 화학. 2007; 55 : 1033-1038. doi : 10.1021 / jf0621469. [ PubMed ] [ 크로스 레퍼런스 ]

64. Otsuki S., Qian W., Ishihara A., Kabe T. 35S 방사성 동위 원소 추적자 방법을 이용한 쥐에서 디메틸 설폰 대사의 해명. Nutr. Res. 2002; 22 : 313-322. doi : 10.1016 / S0271-5317 (01) 00402-X. [ Cross Ref ]

65. Krieger DR, Schwartz HI, Feldman R., Pino I., Vanzant A., Kalman DS, Feldman S., Acosta A., Pardo P., Pezzullo JC 건강한 남자 지원자의 MSM에 대한 약물 동력 학적 투여 량 확대 평가. 마이애미 리서치 어소시에이츠 Miami, FL, USA : 2009. pp. 1-83.

66. Layman DL, Jacob SW 히스 루시 원숭이에 의한 디메틸 술폭 시드의 흡수, 대사 및 배설. 생명 과학. 1985; 37 : 2431-2437. doi : 10.1016 / 0024-3205 (85) 90111-0. [ PubMed ] [ 크로스 레퍼런스 ]

67. Zhang Y.-H., Zhang J.-X. 소변에서 추출한 주요 휘발성 물질은 수컷 쥐의 유전 적 연관성을 나타낼 수 있습니다. Chem. 감각. 2010; 36 : 125-135. doi : 10.1093 / chemse / bjq103. [ PubMed ] [ 크로스 레퍼런스 ]

68. Mattina M., Pignatello J., Swihart R. bobcat (lynx rufus) 소변의 휘발성 성분 식별. J. Chem. Ecol. 1991; 17 : 451-462. doi : 10.1007 / BF00994344. [ PubMed ] [ 크로스 레퍼런스 ]

69. Burger BV, Visser R., Moses A., Le Roux M. 치타의 소변에서 확인 된 원소 황, acinonyx jubatus. J. Chem. Ecol. 2006; 32 : 1347-1352. doi : 10.1007 / s10886-006-9056-5. [ PubMed ] [ 크로스 레퍼런스 ]

70. 애플 리케이션 P., Mmualefe L., McNutt JW 아프리카 야생 개 (lycaon pictus)의 분비물과 배설물에서 휘발성 물질의 확인 J. Chem. Ecol. 2012; 38 : 1450-1461. doi : 10.1007 / s10886-012-0206-7. [ PubMed ] [ 크로스 레퍼런스 ]

71. Dawiskiba T., Deja S., Mulak A., Zabek A., Jawien E., Pawelka D., Banasik M., Mastalerz-Migas A., Balcerzak W., Kaliszewski K. 혈청 및 진단에서의 소변 metabolomic 지문 염증성 장 질환의 World J. Gastroenterol. 2014; 20 : 163-174. doi : 10.3748 / wjg.v20.i1.163. [ PMC 무료 기사 ] [ PubMed ] [ Cross Ref ]

72. Takeuchi A., Yamamoto S., Narai R., Nishida M., Yashiki M., Sakui N., Namera A. 2, 2를 사용한 준비 후 가스 크로마토 그래피 - 질량 분광법에 의한 소변 내 디메틸 술폭 시드 및 디메틸 술폰의 측정 - 디메 톡시 프로판. 바이오 메드. Chromatogr. 2010; 24 : 465-471. doi : 10.1002 / bmc.1313. [ PubMed ] [ 크로스 레퍼런스 ]

73. Coppa M., Martin B., Pradel P., Leotta B., Priolo A., Vasta V. 건식 휘발성 화합물에 대한 건초 식단 또는 다른 고지 방목 시스템의 효과. J. Agric. 식품 화학. 2011; 59 : 4947-4954. doi : 10.1021 / jf2005782. [ PubMed ] [ 크로스 레퍼런스 ]

74. Bakke JM, Figenschou E. 꼬리 글 랜드에서 붉은 사슴 (cervus elaphus) 분비물로부터 휘발성 화합물. J. Chem. Ecol. 1983; 9 : 513-520. doi : 10.1007 / BF00990223. [ PubMed ] [ 크로스 레퍼런스 ]

75. 피게 J., Jonsson P., Adolfsson AN, R. Adolfsson, Nyberg에 L. 인간 타액 대사 체의 오멘 A. NMR 분석 대조군에서 치매 환자를 구별한다. Mol. BioSyst. 2016; 12 : 2562-2571. doi : 10.1039 / C6MB00233A. [ PubMed ] [ 크로스 레퍼런스 ]

76. Cecil KM, Lin A., Ross BD, Egelhoff JC 발달 장애가있는 5 세의 소아에서 생체 내 양자 양자 공명 분광법으로 관찰 된 Methylsulfonylmethane :식이 보충제의 효과. J. Comput. 돕다. 토모. 2002; 26 : 818-820. doi : 10.1097 / 00004728-200209000-00026. [ PubMed ] [ 크로스 레퍼런스 ]

77. Lin A., Nguy CH, Shic F., Ross BD 인간의 두뇌에서 methylsulfonylmethane의 축적 : 다중 핵 자기 공명 분광법에 의한 동정. 독시콜. 레트 사람. 2001; 123 : 169-177. doi : 10.1016 / S0378-4274 (01) 00396-4. [ PubMed ] [ 크로스 레퍼런스 ]

78. Rogovin JL 인간 뇌에서 메틸 술 포닐 메탄의 축적 : 다핵 자기 공명 분광법에 의한 동정. 독시콜. 레트 사람. 2002; 129 : 263-265. doi : 10.1016 / S0378-4274 (02) 00022-X. [ PubMed ] [ 크로스 레퍼런스 ]

79. Rosea SE, Chalk JB, Galloway GJ, Doddrell DM 생체 내 양성자 자기 공명 분광법에 의한 인간 두뇌의 디메틸 술폰 검출. Magn. Reson. 이미징. 2000; 18 : 95-98. doi : 10.1016 / S0730-725X (99) 00110-1. [ PubMed ] [ 크로스 레퍼런스 ]

80. Willemsen MA, Engelke UF, van der Graaf M., Wevers RA Methylsulfonylmethane (MSM) 섭취는 뇌 및 뇌척수액의 양성자 자기 공명 스펙트럼에서 중요한 공명을 일으킨다. 신경과. 2006; 37 : 312-314. doi : 10.1055 / s-2006-955968. [ PubMed ] [ 크로스 레퍼런스 ]

81. Waring R., Emery P. 마약에 대한 반응의 유전 적 기원. Br. Med. 황소. 1995; 51 : 449-461. doi : 10.1093 / oxfordjournals.bmb.a072972. [ PubMed ] [ 크로스 레퍼런스 ]

82. Kistler M., Szymczak W., Fedrigo M., Fiamoncini J., Höllriegl V., Hoeschen C., Klingenspor M., de Angelis MH, Rozman J.식이 요법에서 호흡에 휘발성 유기 화합물에 대한식이 기질의 효과 - 유발 비만 마우스. J. Breath Res. 2014; 8 : 016004. doi : 10.1088 / 1752-7155 / 8 / 1 / 016004. [ PubMed ] [ 크로스 레퍼런스 ]

83. Martin W. In : 인체에서 DMSO와 DMSO2의 자연 발생. Jacob SW, Kappel JE, 편집자. W. Zuckschwerdt Verlag; Germering, 독일 : San Francisco, CA, USA : 1987. pp. 71-77. DMSO International DMSO Workshop, San Francisco, CA, 1987 년 9 월 19 일.

84. Bloomer R., Melcher D., Benjamin R. Serum 건강한 남성에서 msm 치료 1 개월 후의 msm 농도. 클린. Pharmacol. Biopharm. 2015; 4 : 2. doi : 10.4172 / 2167-065X.1000135. [ Cross Ref ]

85. NF-κB와 STAT3의 활성을 억제하여 BMM에서 RANKL에 의한 파골 세포 형성을 억제하는 Joung YH, Darvin P., 강 DY, Nipin S., Byun HJ, Lee C.-H., Lee HK, Yang YM. PLoS ONE. 2016; 11 : e0159891 doi : 10.1371 / journal.pone.0159891. [ PMC 무료 기사 ] [ PubMed ] [ Cross Ref ]

86. 김 Y., 김 D., 임 H., 백 D., 신 H., 김 J. 쥐 macrophages에서 lipopolysaccharide 유발 염증 반응에 methylsulfonylmethane의 소염 효과. Biol. Pharm. 황소. 2009; 32 : 651-656. doi : 10.1248 / bpb.32.651. [ PubMed ] [ 크로스 레퍼런스 ]

87. Kloesch B., Liszt M., Broell J., Steiner G. 디메틸 술폭 시드 및 디메틸 술폰은 인간 연골 세포 세포주 C-28 / I2에서의 IL-6 및 IL-8 발현의 강력한 저해제이다. 생명 과학. 2011; 89 : 473-478. doi : 10.1016 / j.lfs.2011.07.015. [ PubMed ] [ 크로스 레퍼런스 ]

88. Christian F., Smith EL, Carmody RJ 인산화에 의한 nf-κb 서브 유닛의 조절. 세포. 2016; 5 : 12 doi : 10.3390 / cells5010012. [ PMC 무료 기사 ] [ PubMed ] [ Cross Ref ]

89. 로렌스 T. 염증의 핵 인자 NF-κB 경로. 콜드 스프링 하브는 biol 1 : A001651을 시사한다. 콜드 스프링 하브. 전망. Biol. 2009; 1 : a001651. doi : 10.1101 / cshperspect.a001651. [ PMC 무료 기사 ] [ PubMed ] [ Cross Ref ]

90. Ahn H., Kim J., Lee M.-J., Kim YJ, Cho Y.-W., Lee G.-S. 메틸 술 포닐 메탄은 NLRP3 인플라 좀솜 활성화를 억제합니다. 시토 킨. 2015; 71 : 223-231. doi : 10.1016 / j.cyto.2014.11.001. [ PubMed ] [ 크로스 레퍼런스 ]

91. Oshima Y., Amiel D., Theodosakis J. 체외에서 인간 연골 세포에 대한 증류 된 methylsulfonylmethane (msm)의 영향. 골격. Cartil. 2007; 15 : C123. doi : 10.1016 / S1063-4584 (07) 61846-9. [ Cross Ref ]

92. Tousoulis D., Kampoli A.-M., Tentolouris Nikolaos Papageorgiou C., Stefanadis C. 내피 기능에 대한 산화 질소의 역할. Curr. Vasc. Pharmacol. 2012; 10 : 4-18 절. doi : 10.2174 / 157016112798829760. [ PubMed ] [ 크로스 레퍼런스 ]

93. Coleman J. Nitric oxide : 비만 세포 활성화 및 비만 세포 매개 염증 조절 인자. 클린. 특급. Immunol. 2002; 129 : 4-10. doi : 10.1046 / j.1365-2249.2002.01918.x. [ PMC 무료 기사 ] [ PubMed ] [ Cross Ref ]

94. Abderrazak A., Syrovets T., Couchie D., El Hadri K., Friguet B., Simmet T., Rouis M. NLRP3 inflammasome : 위험 신호 센서에서부터 산화 스트레스와 염증성 질환의 조절 노드에 이르기까지. Redox Biol. 2015; 4 : 296-307. doi : 10.1016 / j.redox.2015.01.008. [ PMC 무료 기사 ] [ PubMed ] [ Cross Ref ]

95. 그는 Y., Hara H., Núñez G. NLRP3 inflammasome 활성화 메커니즘 및 조절. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2016; 41 : 1012-1021. doi : 10.1016 / j.tibs.2016.09.002. [ PMC 무료 기사 ] [ PubMed ] [ Cross Ref ]

96. Dunn JD, Alvarez LA, Zhang X., Soldati T. 반응성 산소 종과 미토콘드리아 : 세포 항상성의 연결. Redox Biol. 2015; 6 : 472-485. doi : 10.1016 / j.redox.2015.09.005. [ PMC 무료 기사 ] [ PubMed ] [ Cross Ref ]

97. Beilke MA, Collins-Lech C., Sohnle PG 인간 호중구의 산화 기능에 디메틸 술폭 시드가 미치는 영향. J. Lab. 클린. Med. 1987; 110 : 91-96. [ PubMed ]

98. Kastl L., 사우어 S., 루퍼트 T., T. BEISSBARTH 베커 M., D. SUSS, 크래 머는 P., Gülow K. TNF-α는 미토콘드리아의 언 커플 링을 매개로 ROS 및 의존성 세포 이동을 향상 NF-ĸB 간세포에서의 활성화. FEBS Lett. 2014; 588 : 175-183. doi : 10.1016 / j.febslet.2013.11.033. [ PubMed ] [ 크로스 레퍼런스 ]

99. Joung YH, Na YM, Yoo YB, Darvin P., Sp N., Kang DY, Kim SY, Kim HS, Choi YH, Lee HK ag490, jak2 억제제와 methylsulfonylmethane의 조합은 시냅스를 통한 방광 종양의 성장을 상승적으로 억제한다. jak2 / STAT3 경로. Int. J. Oncol. 2014; 44 : 883-895. [ PubMed ]

100. Lim EJ, 홍 DY, 박 JH, 정영호, Darvin P., 김윤진, Na YM, 황제홍, Ye S.-K., Moon E.-S. 메틸 술 포닐 메탄은 STAT3 및 STAT5b 경로를 하향 조절함으로써 유방암 성장을 억제합니다. PLoS ONE. 2012; 7 : e33361 doi : 10.1371 / journal.pone.0033361. [ PMC 무료 기사 ] [ PubMed ] [ Cross Ref ]

101. Nipin S., Darvin P., Yoo YB, Joung YH, Kang DY, 김민수, 황시성, 김동수, 김동욱, 이호석 methylsulfonylmethane과 tamoxifen의 조합은 jak2 / STAT5b 경로를 억제하고 상승적으로 종양 성장을 억제한다 및 er 양성 유방암 이종 이식에 전이. BMC 암. 2015; 15 : 474 [ PMC 무료 기사 ] [ PubMed ]

102. Dickson BJ Mater의 논문. Western Ontario 대학; London, ON, Canada : 2016. 8 월, ROS 매개 분화에서 NADPH 옥시 다제의 역할.

103. Höll M., Koziel R., Schäfer G., Pircher H., Pauck A., Hermann M., Klocker H., Jansen-Dürr P., Sampson N. Ros 신호의 nadph oxidase 5는 증식과 생존을 조절한다 전립선 암종 세포의 Mol. Carcinog. 2016; 55 : 27-39. doi : 10.1002 / mc.22255. [ PMC 무료 기사 ] [ PubMed ] [ Cross Ref ]

104. Redza-Dutordoir M., Averill-Bates DA 활성 산소 종에 의한 세포 자멸 신호 전달 경로의 활성화. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Cell Res. 2016; 1863 : 2977-2992. doi : 10.1016 / j.bbamcr.2016.09.012. [ PubMed ] [ 크로스 레퍼런스 ]

105 Manea 선수 A., 타나 LI, Raicu M., M. Simionescu JAK / STAT 신호 경로는 인간 대동맥 평활근 세포 및 nox1 nox4 기반 NADPH 옥시 다제를 조절한다. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2010; 30 : 105-112. doi : 10.1161 / ATVBAHA.109.193896. [ PubMed ] [ 크로스 레퍼런스 ]

106. 총 A. 미토콘드리아 대사 조절 인자로서의 BCL-2 계열 단백질. Biochim. Biophys. 액타. 2016; 1857 : 1243-1246. doi : 10.1016 / j.bbabio.2016.01.017. [ PubMed ] [ 크로스 레퍼런스 ]

107. Karabay AZ, Aktan F., Sunguroğlu A., Buyukbingol Z. 메틸 술 포닐 메탄은 p53, Bax, Bcl-2, 시토크롬 C 및 PARP 단백질을 표적으로하여 lps / ifn-γ 활성화 된 264.7 대 식세포 유사 세포의 세포 사멸을 조절한다. Immunopharmacol. Immunotoxicol. 2014; 36 : 379-389. doi : 10.3109 / 08923973.2014.956752. [ PubMed ] [ 크로스 레퍼런스 ]

108. Liu D., Xu Y. P53, 산화 스트레스 및 노화. 항산화. 산화 환원 신호. 2011; 15 : 1669-1678. doi : 10.1089 / ars.2010.3644. [ PMC 무료 기사 ] [ PubMed ] [ Cross Ref ]

109. Kim S.-H., Smith AJ, Tan J., Shytle RD, Giunta B. Msm은 글루타티온 순환의 재조정을 통해 HIV-1 tat 유도 신경 세포 산화 스트레스를 완화시킨다. 오전. J. Transl. Res. 2015; 7 : 328. [ PMC 무료 기사 ] [ PubMed ]

110. 장 H., 데이비스 KJ, Forman HJ 노화에있는 산화 스트레스 반응 및 nrf2 신호. 자유 라디칼. Biol. Med. 2015; 88 : 314-336. doi : 10.1016 / j.freeradbiomed.2015.05.036. [ PMC 무료 기사 ] [ PubMed ] [ Cross Ref ]

111. Ma Q. 산화 스트레스와 독성에서의 NRF2의 역할. 아누. Pharmacol. 독시콜. 2013; 53 : 401-426. doi : 10.1146 / annurev-pharmtox-011112-140320. [ PMC 무료 기사 ] [ PubMed ] [ Cross Ref ]

112. Grimble RF 인간의 면역 기능에 미치는 황산 아미노 섭취의 영향. J. Nutr. 2006; 136 : 1660S-1665S. [ PubMed ]

113. Parcell S. 인간 영양과 의학 분야의 유황. 대체. Med. Rev 2002; 7 : 22-44. [ PubMed ]

114. Ramoutar RR, Brumaghim JL 무기 항 셀레늄, 옥소 - 유황 및 옥소 - 셀레늄 화합물의 항산화 및 항암 작용 및 기작. Cell Biochem. Biophys. 2010; 58 : 1-23. doi : 10.1007 / s12013-010-9088-x. [ PubMed ] [ 크로스 레퍼런스 ]

(115) Gabay C. 인터루킨 -6 및 만성 염증. 관절염 치료제. 테러. 2006; 8 : S3. doi : 10.1186 / ar1917. [ PMC 무료 기사 ] [ PubMed ] [ Cross Ref ]

116 Candussio L., Klugmann F., Decorti G., BEVILACQUA S., 발디니 L. 디메틸 설폭 사이드는 다양한 화학 물질에 의해 유도 히스타민 방출을 억제한다. 에이전트 작업. 1987; 20 : 17-28. doi : 10.1007 / BF01965621. [ PubMed ] [ 크로스 레퍼런스 ]

117. Layman DL 체외에서 혈관 평활근과 내피 세포에 대한 dimethyl sulfoxide와 dimethyl sulfone의 성장 억제 효과. In Vitro Cell. Dev. Biol. 1987; 23 : 422-428. doi : 10.1007 / BF02623858. [ PubMed ] [ 크로스 레퍼런스 ]

118. Alam SS, Layman DL 배양 된 대동맥 내피 세포에서 프로스타글린 생산의 디메틸 술폭 시드 억제. 앤. NY Acad. Sci. 1983; 411 : 318-320. doi : 10.1111 / j.1749-6632.1983.tb47314.x. [ PubMed ] [ 크로스 레퍼런스 ]

119. Jafari N., Bohlooli S., Mohammadi S., Mazani M. 위장관 (AGS, HEPG2 및 KEYSE-30) 암 세포주에서 메틸 술 포닐 메탄의 세포 독성. J. Gastrointest. 암. 2012; 43 : 420-425. doi : 10.1007 / s12029-011-9291-z. [ PubMed ] [ 크로스 레퍼런스 ]

120. Kim J.-H., Shin H.-J., Ha H.-L., Park Y.-H., Kwon T.-H., Jung M.-R., Moon H.-B. , Cho E.S., Son H.-Y., Yu D.-Y. Methylsulfonylmethane은 apoptosis의 활성화를 통해 간 종양 발달을 억제합니다. World J. Hepatol. 2014; 6 : 98-106. [ PMC 무료 기사 ] [ PubMed ]

121. Karabay AZ, Koc A., Ozkan T., Hekmatshoar Y., Sunguroglu A., Aktan F., Buyukbingol Z. 메틸 술 포닐 메탄은 HCT-116 결장암 세포에서 P53 독립적 인 세포 사멸을 유도한다. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016; 17 : 1123 doi : 10.3390 / ijms17071123. [ PMC 무료 기사 ] [ PubMed ] [ Cross Ref ]

122. Caron JM, Bannon M., Rosshirt L., O'donovan L. Methyl sulfone은 전이성 쥐 유방암 세포주 및 인간 유방암 조직에서 항암 활성을 나타낸다. 부분 I : Murine 4t1 (66CL-4) 세포주 . 화학 요법. 2013; 59 : 14-23. [ PubMed ]

123 캐론은 JM, 캐론 JM 메틸 술폰는 유방암 세포 및 흑색 종 세포에서 여러 저산소증 및 비 - 저산소증 유도 전이성 타겟을 막았다. PLoS ONE. 2015; 10 : e0141565 doi : 10.1371 / journal.pone.0141565. [ PMC 무료 기사 ] [ PubMed ] [ Cross Ref ]

124. Touchberry CD, Von Schulze A., Amat-Fernandez C., Lee H., Chow Y., Wetmore LA Methylsulfonylmethane (MSM) 치료는 C 2 C 12 상처 봉합을 향상시키고 세포를 산화 스트레스로부터 보호한다. FASEB J. 2016; 30 : 1245.20.

125 카론 JM, 밴논 M., Rosshirt L. 루이스 J., Monteagudo L., 캐론 JM, Sternstein GM 메틸 술폰 전이성 cloudman S-91 (M3) 쥐 흑색 종 전이 특성의 손실 및 정상적인 표현형의 재 출현을 유도 세포주. PLoS ONE. 2010; 5 : e11788 doi : 10.1371 / journal.pone.0011788. [ PMC 무료 기사 ] [ PubMed ] [ Cross Ref ]

126. Caron JM, Monteagudo L., Sanders M., Bannon M., Deckers PJ Methyl sulfone은 전이성 쥐 유방암 세포주 및 인간 유방암 조직 - 제 2 부 : 인간 유방암 조직에서 항암 활성을 나타낸다. 화학 요법. 2013; 59 : 24-34. [ PubMed ]

127. Richmond VL 기니 피그 혈청 단백질에 메틸 술 포닐 메탄 황을 도입. 생명 과학. 1986; 39 : 263-268. doi : 10.1016 / 0024-3205 (86) 90540-0. [ PubMed ] [ 크로스 레퍼런스 ]

128. Cloutier J.-F., Castonguay A., O'Connor TR, Drouin R. 알킬화제 및 염색질 구조는 알킬 퓨린의 서열 상황 의존적 형성을 결정한다. J. Mol. Biol. 2001; 306 : 169-188. doi : 10.1006 / jmbi.2000.4371. [ PubMed ] [ 크로스 레퍼런스 ]

129. Kawai K., Li Y.-S., Song M.-F., Kasai H. 히드 록실 라디칼에 의해 유발 된 디메틸 술폭 사이드와 메티오닌 술폭 시드에 의한 DNA 메틸화 및 후성 변형에 대한 함의. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 레트 사람. 2010; 20 : 260-265. doi : 10.1016 / j.bmcl.2009.10.124. [ PubMed ] [ 크로스 레퍼런스 ]

130. Hootman JM, Helmick CG, Barbour KE, Theis KA, Boring MA 2015-2040 년 성인의자가 진단 된 관절염 및 관절염에 기인 한 활동 제한의 자체보고 된 예상 유병률을 업데이트했습니다. 관절염 류마티스 관절염. 2016; 68 : 1582-1587. doi : 10.1002 / art.39692. [ PubMed ] [ 크로스 레퍼런스 ]

131. Hasegawa T., Ueno S., Kumamoto S., Yoshikai Y. dba / 1j 마우스의 II 형 콜라겐 유발 성 관절염에 대한 methylsulfonylmethane (MSM)의 억제 효과. Jpn. Pharmacol. 테러. 2004; 32 : 421-428.

132. Amiel D., Healey RM, Oshima Y. 골관절염 (OA)의 발달에 대한 methylsulfonylmethane (MSM)의 평가 : 동물 연구. FASEB J. 2008; 22 : 1094.3.

133. Arafa NM, Hamuda HM, Melek ST, Darwish SK 급성 및 만성 류마티스 성 관절염 쥐 모델에서에 치나 세아 추출물 또는 복합 글루코사민, 콘드로이틴 및 메틸 술 포닐 메탄 보충제의 효과. 독시콜. 공업 건강. 2013; 29 : 187-201. doi : 10.1177 / 0748233711428643. [ PubMed ] [ 크로스 레퍼런스 ]

134. Usha P., Naidu M. 골관절염에서 구강 글루코사민, 메틸 술 포닐 메탄 및 이들의 병용에 대한 무작위 이중 맹검, 평형 위약 대조 연구. 클린. Drug Investig. 2004; 24 : 353-363. doi : 10.2165 / 00044011-200424060-00005. [ PubMed ] [ 크로스 레퍼런스 ]

135. Debi R., Fichman G., Ziv YB, Kardosh R., Debbi E., Halperin N., Agar G. 무릎 골관절염에서 msm의 역할 : 이중 맹검, 무작위, 전향 적 연구. 골격. Cartil. 2007; 15 : C231. doi : 10.1016 / S1063-4584 (07) 62057-3. [ Cross Ref ]

136. Pagonis TA, Givissis PA, Kritis AC, Christodoulou AC 골관절염 성 관절과 운동성에 미치는 메틸 술 포닐 메탄의 효과. Int. J. Orthop. 2014; 1 : 19 ~ 24.

137. Nakasone Y., Watabe K., Watanabe K., Tomonaga A., Nagaoka I., Yamamoto T., Yamaguchi H. 증상이있는 슬관절 골관절염 환자에서 콘드로이틴 설페이트와 항산화 미량 영양소를 포함한 글루코사민 계 복합제의 효과 : 파일럿 연구. 특급. 테러. Med. 2011; 2 : 893-899. [ PMC 무료 기사 ] [ PubMed ]

138. Vidyasagar S., Mukhyaprana P., Shashikiran U., Sachidananda A., Rao S., Bairy KL, Adiga S., Jayaprakash B. 무릎 관절염에서 글루코사민 콘드로이친 황산염 - 메틸 술 포닐 메탄 (MSM)의 효능 및 내약성 인도 환자에서. 이란. J. Pharmacol. 테러. 2004; 3 : 61-65.

139. Magrans-Courtney T., Wilborn C., Rasmussen C., Ferreira M., Greenwood L., Campbell B., Kerksick CM, Nassar E., Li R., Iosia M.식이 요법의 유형 및 글루코사민 보충 효과 , chondroitin 및 msm에 대한 저항성 운동과 체중 감소 프로그램을 시작하는 무릎 골관절염 여성의 신체 조성, 기능 상태 및 건강 지표에 대한 정보를 제공합니다. J. Int. Soc. 스포츠 너트. 2011; 8 : 8. doi : 10.1186 / 1550-2783-8-8. [ PMC 무료 기사 ] [ PubMed ] [ Cross Ref ]

140. Notarnicola A., Maccagnano G., Moretti L., Pesce V., Tafuri S., Fiore A., Moretti B. Methylsulfonylmethane 및 boswellic acid 대 무릎 관절염 치료제의 글루코사민 : 무작위 시험. Int. J. Immunopathol. Pharmacol. 2016; 29 : 140-146. doi : 10.1177 / 0394632015622215. [ PubMed ] [ 크로스 레퍼런스 ]

141. Xie Q, Shi R., Xu G., Cheng L., Shao L., Rao J. 골관절염 환자를위한 관절통에 대한 AR7 관절 복합체의 효과 : 중국 상하이에서 3 개월간 연구 한 결과. Nutr. J. 2008; 7 : 31. doi : 10.1186 / 1475-2891-7-31. [ PMC 무료 기사 ] [ PubMed ] [ Cross Ref ]

142. Amirshahrokhi K., Bohlooli S., Chinifroush M. 쥐의 실험적인 대장염에 대한 methylsulfonylmethane의 효과. 독시콜. Appl. Pharmacol. 2011; 253 : 197-202. doi : 10.1016 / j.taap.2011.03.017. [ PubMed ] [ 크로스 레퍼런스 ]

143. Amirshahrokhi K., Bohlooli S. 마우스의 파라 캇 유발 급성 폐 및 간 손상에 대한 메틸 술 포닐 메탄의 영향. 염증. 2013; 36 : 1111-1121. doi : 10.1007 / s10753-013-9645-8. [ PubMed ] [ 크로스 레퍼런스 ]

144. Kamel R., El Morsy EM 사염화탄소에 의한 쥐의 급성 간 손상에 대한 methylsulfonylmethane의 간 보호 효과. 아치. Pharm. Res. 2013; 36 : 1140-1148. doi : 10.1007 / s12272-013-0110-x. [ PubMed ] [ 크로스 레퍼런스 ]

145. Moore R., Morton J. dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) 또는 methylsulfonylmethane (MSM)을 섭취 한 mrl / 1pr 마우스에서 염증성 관절 질환 감소 . Proc. 1985; 44 : 530.

(146) 염증성 질환으로 Berenbaum F. 골관절염 (퇴행성 관절염은 골관절염하지 않습니다!) Osteoarthr. Cartil. 2013; 21 : 16-21. doi : 10.1016 / j.joca.2012.11.012. [ PubMed ] [ 크로스 레퍼런스 ]

147. Sophia Fox A.J., Bedi A., Rodeo S.A. The basic science of articular cartilage: Structure, composition, and function. Sports Health. 2009;1:461–468. doi: 10.1177/1941738109350438. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Cross Ref]

148. Kobayashi M., Squires G.R., Mousa A., Tanzer M., Zukor D.J., Antoniou J., Feige U., Poole A.R. Role of interleukin-1 and tumor necrosis factor α in matrix degradation of human osteoarthritic cartilage. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2005;52:128–135. doi: 10.1002/art.20776. [PubMed] [Cross Ref]

149. Ezaki J., Hashimoto M., Hosokawa Y., Ishimi Y. Assessment of safety and efficacy of methylsulfonylmethane on bone and knee joints in osteoarthritis animal model. J. Bone Miner. Metab. 2013;31:16–25. doi: 10.1007/s00774-012-0378-9. [PubMed] [Cross Ref]

150. Murav’ev I., Venikova M., Pleskovskaia G., Riazantseva T., Sigidin I. Effect of dimethyl sulfoxide and dimethyl sulfone on a destructive process in the joints of mice with spontaneous arthritis. Patol. Fiziol. Eksp. Ter. 1990;2:37–39. [PubMed]

151. Maher A.D., Coles C., White J., Bateman J.F., Fuller E.S., Burkhardt D., Little C.B., Cake M., Read R., McDonagh M.B. 1H nmr spectroscopy of serum reveals unique metabolic fingerprints associated with subtypes of surgically induced osteoarthritis in sheep. J. Proteome Res. 2012;11:4261–4268. doi: 10.1021/pr300368h. [PubMed] [Cross Ref]

152. Melcher D.A., Lee S.-R., Peel S.A., Paquette M.R., Bloomer R.J. Effects of methylsulfonylmethane supplementation on oxidative stress, muscle soreness, and performance variables following eccentric exercise. Gazz. Med. Ital.-Arch. Sci. Med. 2016;175:1–13.

153. Gumina S., Passaretti D., Gurzi M., Candela V. Arginine l-alpha-ketoglutarate, methylsulfonylmethane, hydrolyzed type i collagen and bromelain in rotator cuff tear repair: A prospective randomized study. Curr. Med. Res. Opin. 2012;28:1767–1774. doi: 10.1185/03007995.2012.737772. [PubMed] [Cross Ref]

154. Higler M., Brommer H., L’ami J., Grauw J., Nielen M., Weeren P., Laverty S., Barneveld A., Back W. The effects of three-month oral supplementation with a nutraceutical and exercise on the locomotor pattern of aged horses. Equine Vet. J. 2014;46:611–617. doi: 10.1111/evj.12182. [PubMed] [Cross Ref]

155. Notarnicola A., Tafuri S., Fusaro L., Moretti L., Pesce V., Moretti B. The “mesaca” study: Methylsulfonylmethane and boswellic acids in the treatment of gonarthrosis. Adv. Ther. 2011;28:894–906. doi: 10.1007/s12325-011-0068-3. [PubMed] [Cross Ref]

156. Tant L., Gillard B., Appelboom T. 허리 통증에 대한 글루코사민 복합체의 효과에 대한 무작위, 대조군 시험 연구. Curr. 테러. Res. 2005; 66 : 511-521. doi : 10.1016 / j.curtheres.2005.12.009. [ PMC 무료 기사 ] [ PubMed ] [ Cross Ref ]

157. Stuber K., Sajko S., Kristmanson K. 척수 퇴행성 관절 질환 및 퇴행성 디스크 질환에 대한 글루코사민, 콘드로이친 및 메틸 술 포닐 메탄의 효용성 : 체계적인 검토. J. 캔. Chiropr. Assoc. 2011; 55 : 47. [ PMC 무료 기사 ] [ PubMed ]

158. Lewis PB, Ruby D., Bush-Joseph CA 근육통과 지연 발병 근육통. 클린. 스포츠. Med. 2012; 31 : 255-262. doi : 10.1016 / j.csm.2011.09.009. [ PubMed ] [ 크로스 레퍼런스 ]

159 Barmaki S., Bohlooli S., Khoshkhahesh F., 운동 유발 성 근육 손상 및 총 항산화 제 용량에 유기 유황의 보충 Nakhostin-Roohi B. 효과. J. Sports Med. Phys. 적당한. 2012; 52 : 170. [ PubMed ]

160. Kalman DS, Feldman S., Samson A., Krieger DR 운동 유발 성 불편 / 통증에 대한 msm의 무작위 이중 맹검 위약 대조 평가. FASEB J. 2013; 27 : 1076-1077.

161. Kalman DS, Feldman S., Scheinberg AR, Krieger DR, Bloomer RJ 건강한 남성의 운동 회복 및 수행 지표에 대한 methylsulfonylmethane의 영향 : 예비 연구. J. Int. Soc. 스포츠 너트. 2012; 9 : 46. doi : 10.1186 / 1550-2783-9-46. [ PMC 무료 기사 ] [ PubMed ] [ Cross Ref ]

162. Withee ED, Tippens KM, Dehen R., Hanes D. 운동 유발 근육 및 관절통에 대한 msm의 효과 : 예비 연구. J. Int. Soc. 스포츠 너트. 2015; 12 : P8. doi : 10.1186 / 1550-2783-12-S1-P8. [ Cross Ref ]

163 Bohlooli S., 모하마디 S., Amirshahrokhi K., Mirzanejad-ASL의 H., M. Yosefi, 모하마디-네이의 A. 쥐의 aceta minophen - 유도 간독성에 유기 유황 전처리 Chinifroush MM 효과. 이란. J. Basic Med. Sci. 2013; 16 : 896. [ PMC 무료 기사 ] [ PubMed ]

164. Marañon G., Muñoz-Escassi B., Manley W., García C., Cayado P., De la Muela MS, Olábarri B., León R., Vara E. 메틸 술 포닐 메탄 보충제가 바이오 마커에 미치는 영향 점프 운동을 한 스포츠 말의 산화 스트레스. Acta Vet. 스캔. 2008; 50 : 45. doi : 10.1186 / 1751-0147-50-45. [ PMC 무료 기사 ] [ PubMed ] [ Cross Ref ]

165. Mohammadi S., Najafi M., Hamzeiy H., Maleki-Dizaji N., Pezeshkian M., Sadeghi-Bazargani H., Darabi M., Mostafalou S., Bohlooli S., Garjani A. 메틸 술 포닐 메탄의 보호 효과 monocrotaline에 의한 폐 고혈압 흰쥐에서의 혈역학 및 산화 스트레스. Adv. Pharmacol. Sci. 2012; 2012 : 507278. doi : 10.1155 / 2012 / 507278. [ PMC 무료 기사 ] [ PubMed ] [ Cross Ref ]

166 생쥐 DiSilvestro RA, DiSilvestro DJ, DJ DiSilvestro 유기 유황 (MSM)은 상승 된 흡기 간 글루타치온 생산 부분적 사염화탄소 - 유도 간 손상에 대해 보호한다. FASEB J. 2008; 22 : 445.8.

167. Nakhostin-Roohi B., Barmaki S., Khoshkhahesh F., Bohlooli S. 숙련되지 않은 건강한 남성에서 급성 운동으로 인한 산화 스트레스에 대한 methylsulfonylmethane의 만성 보충제 효과. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2011; 63 : 1290-1294. doi : 10.1111 / j.2042-7158.2011.01314.x. [ PubMed ] [ 크로스 레퍼런스 ]

168. Nakhostin-Roohi B., Niknam Z., Vaezi N., Mohammadi S., Bohlooli S. 급성 철저한 운동에 따른 산화 스트레스에 대한 메틸 술 포닐 메탄의 단일 용량 투여 효과. 이란. J. Pharm. Res. 2013; 12 : 845-853. [ PMC 무료 기사 ] [ PubMed ]

169. Zhang M., Wong IG, Gin JB, Ansari NH 지역 edta 킬레이트 치료를위한 투과 촉진제로서 methylsulfonylmethane의 평가. Drug Deliv. 2009; 16 : 243-248. doi : 10.1080 / 10717540902896362. [ PubMed ] [ 크로스 레퍼런스 ]

170. Liu P., Zhang M., Shoeb M., Hogan D., Tang L., Syed M., Wang C., Campbell G., 투자 촉진제와 결합 된 Ansari N. Metal chelator는 산화 스트레스 관련 신경 퇴행을 개선한다. 상승 된 안압을 가진 쥐 눈. 자유 라디칼. Biol. Med. 2014; 69 : 289-299. doi : 10.1016 / j.freeradbiomed.2014.01.039. [ PMC 무료 기사 ] [ PubMed ] [ Cross Ref ]

171. Wang CZ, El Ayadi A., Goswamy J., Finnerty CC, Mifflin R., Sousse L., Enkhbaatar P., Papaconstantinou J., Herndon DN, Ansari NH 피부에 국소 적으로 작용하는 금속 킬 레이터 놋쇠 빗 굽기. 화상. 2015; 41 : 1775-1787. doi : 10.1016 / j.burns.2015.08.012. [ PMC 무료 기사 ] [ PubMed ] [ Cross Ref ]

172 장 M., M. Shoeb 류 P., 샤오 T. 호건 D., 웡 IG 캠벨 GA, 안사 NH 금속 킬레이트 화제 요법 당뇨병 백내장 산화 유도 독성을 개선한다. J. Toxicol. 환경. 건강 파트 A. 2011; 74 : 380-391. doi : 10.1080 / 15287394.2011.538835. [ PubMed ] [ 크로스 레퍼런스 ]

173. Tripathi R., Gupta S., Rai S., Mittal P. 이중 맹검, 위약 대조 연구에서 부종 및 산화 스트레스에 대한 메틸 술 포닐 메탄 (MSM), EDTA의 국소 적용 효과. 세포. Mol. Biol. 2011; 57 : 62-69. [ PubMed ]

174. Kantor ED, Ulrich CM, Owen RW, Schmezer P., Neuhouser ML, Lampe JW, Peters U., Shen DD, Vaughan TL, White E. 산화 스트레스 및 DNA 손상의 특수 보충제 사용 및 생물학적 측정. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. 이전 2013; 22 : 2313-2322. doi : 10.1158 / 1055-9965.EPI-13-0470. [ PMC 무료 기사 ] [ PubMed ] [ Cross Ref ]

175. Manzella N., Bracci M., Strafella E., Staffolani S., Ciarapica V., Copertaro A., Rapisarda V., Ledda C., Amati M., 8-oxoguanine DNA 손상 수리의 Valentino M. Circadian 변조 . Sci. Rep 2015; 5 : 13752. doi : 10.1038 / srep13752. [ PMC 무료 기사 ] [ PubMed ] [ Cross Ref ]

176. 계절 알레르기 비염 치료제 Gaby AR Methylsulfonylmethane : 꽃가루 조사와 설문지에 더 많은 자료가 필요하다. J. Altern. 보어. Med. 2002; 8 : 229. doi : 10.1089 / 10755530260127925. [ PubMed ] [ 크로스 레퍼런스 ]

177. Anthonavage M., Benjamin RL, Withee ED 피부 건강과 주름 감소에 대한 methylsulfonylmethane의 경구 보충 효과. Nat. Med. J. 2015; 7

178. Berardesca E., Cameli N., Primavera G., Carrera M. 새로운 50 % 피루브산 껍질로 치료 한 후 피부 개선에 대한 임상 적 및 도구 적 평가. Dermatol. 수술. 2006; 32 : 526-531. [ PubMed ]

179. Berardesca E., Cameli N., Cavallotti C., Levy JL, Piérard GE, Paoli Ambrosi G. 주사제 관리에서 silymarin과 methylsulfonylmethane의 복합 효과 : 임상 적 및 도구 적 평가. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2008; 7 : 8-14. doi : 10.1111 / j.1473-2165.2008.00355.x. [ PubMed ] [ 크로스 레퍼런스 ]

180. Fleck CA 소화관 병 치료 : 사례 연구. Ostomy 상처 관리. 2006; 52 : 82-90. [ PubMed ]

181. Kang DY, Darvin P., Yoo YB, Joung YH, Sp N., Byun HJ, 양 YM Methylsulfonylmethane은 유방암 세포에서 STAT5b를 통해 her2 발현을 억제한다. Int. J. Oncol. 2016; 48 : 836-842. doi : 10.3892 / ijo.2015.3277. [ PubMed ] [ 크로스 레퍼런스 ]

182. 박 DJ, 토마스 뉴저지, 윤윤영, 유성 혈관 내피 세포 성장 인자 위암 억제. 위암. 2015; 18 : 33-42. doi : 10.1007 / s10120-014-0397-4. [ PubMed ] [ 크로스 레퍼런스 ]

183. Werner H., Bruchim I. Igf-1 및 brca1 신호 전달 경로. 랜싯. Oncol. 2012; 13 : e537-e544. doi : 10.1016 / S1470-2045 (12) 70362-5. [ PubMed ] [ 크로스 레퍼런스 ]

184 맥케이브 D., P. O'Dwyer 낫 Santanello B., Woltering E., 아부 - 이싸 H., dimethylbenzanthracene 유발 쥐 유방 암의 화학 예방 제임스 A. 극성 용매. 아치. 수술. 1986; 121 : 1455-1459. doi : 10.1001 / archsurg.1986.01400120105017. [ PubMed ] [ 크로스 레퍼런스 ]

185 O'Dwyer PJ, 맥케이브 DP 낫 Santanello BJ, Woltering EA, 클라우 K. 마틴 E., 1,2- 디메틸 - 유도 결장암의 화학적 예방 극성 용매의 사용은 주니어. 암. 1988; 62 : 944-948. DOI : 10.1002 / 1097-0142 (19880901) 62 : 5 <944 :: AID-CNCR2820620516> 3.0.CO; 2-A. [ PubMed ] [ 크로스 레퍼런스 ]

186 Satia JA, Littman A., Slatore CG, Galanko JA, White E. 비타민 및 생활 습관 연구에서 폐 및 대장 암 위험이있는 약초 및 전문 보충제 협회. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. 이전 2009; 18 : 1419-1428. doi : 10.1158 / 1055-9965.EPI-09-0038. [ PMC 무료 기사 ] [ PubMed ] [ Cross Ref ]

187. Horvath K., Noker P., Somfai-Relle S., Glavits R., Financsek I., Schauss A. 쥐의 메틸 술 포닐 메탄의 독성. 식품 화학. 독시콜. 2002; 40 : 1459-1462. doi : 10.1016 / S0278-6915 (02) 00086-8. [ PubMed ] [ 크로스 레퍼런스 ]

188. Magnuson B., Appleton J., Ryan B., Matulka R. 쥐의 methylsulfonylmethane에 대한 경구 발육 독성 연구. 식품 화학. 독시콜. 2007; 45 : 977-984. doi : 10.1016 / j.fct.2006.12.003. [ PubMed ] [ 크로스 레퍼런스 ]

189. Morton JI, Siegel BV 쥐의자가 면역 림프 증식 성 질환에 대한 경구 용 디메틸 술폭 사이드와 디메틸 술폰의 효과 1. Proc. Soc. 특급. Biol. Med. 1986; 183 : 227-230. doi : 10.3181 / 00379727-183-42409. [ PubMed ] [ 크로스 레퍼런스 ]

190 타키 야마 K., 코니시 F., Y. 나카시마, 구마 S. 마루야마 I. 단일 및 유기 유황 마우스에서 13 주 반복 경구 투여 독성 연구. 오야 야쿠리. 2010; 79 : 23-30.

191. Brim TA, Center V., Wynn S., Springs S., Gray L., Brown L. 관절 보조제의 우발적 인 과량 투여에 대한 추가 정보. J. Am. 수의사. Med. Assoc. 2010; 236 : 1061. [ PubMed ]

192. Khan SA, McLean MK, Gwaltney-Brant S. 강아지의 공동 보충제의 우발적 인 과다 복용. J. Am. 수의사. Med. Assoc. 2010; 236 : 509. [ PubMed ]

193. Gaval-Cruz M., Weinshenker D. disulfiram 유도 코카인 금욕의 메커니즘 : Antabuse 및 코카인 재발. Mol. Interv. 2009; 9 : 175. doi : 10.1124 / mi.9.4.6. [ PMC 무료 기사 ] [ PubMed ] [ Cross Ref ]

194. Wang M., Anderson G., Nowicki D. 여성 sprague-dawley (SD)에서 dmba에 의해 유도 된 화학 발암 기의 시작 단계에서 유방암 예방에 대한 타히티안 노니 주스 (TNJ)와 메틸 술 포닐 메탄 (MSM) 쥐. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. 이전 2003; 12 : 1354S.

195. Sousa-Lima I., Park S.-Y., 정 M., 정 HJ, 강 M.-C., Gaspar JM, 서 JA, Macedo MP, Park KS, Mantzoros C. Methylsulfonylmethane (MSM), organosulfur 화합물은 생쥐의 비만 유발 대사 장애에 효과적입니다. 대사. 2016; 65 : 1508-1521. doi : 10.1016 / j.metabol.2016.07.007. [ PubMed ] [ 크로스 레퍼런스 ]

--------------------------------------------------------------------------

Methylsulfonylmethane: Applications and Safety of a Novel Dietary Supplement

Matthew Butawan,1 Rodney L. Benjamin,2 and Richard J. Bloomer1,*

Abstract

Methylsulfonylmethane (MSM) has become a popular dietary supplement used for a variety of purposes, including its most common use as an anti-inflammatory agent. It has been well-investigated in animal models, as well as in human clinical trials and experiments. A variety of health-specific outcome measures are improved with MSM supplementation, including inflammation, joint/muscle pain, oxidative stress, and antioxidant capacity. Initial evidence is available regarding the dose of MSM needed to provide benefit, although additional work is underway to determine the precise dose and time course of treatment needed to provide optimal benefits. As a Generally Recognized As Safe (GRAS) approved substance, MSM is well-tolerated by most individuals at dosages of up to four grams daily, with few known and mild side effects. This review provides an overview of MSM, with details regarding its common uses and applications as a dietary supplement, as well as its safety for consumption.

Keywords: methylsulfonylmethane, MSM, dimethyl sulfone, inflammation, joint pain

1. Description and History of MSM

Methylsulfonylmethane (MSM) is a naturally occurring organosulfur compound utilized as a complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) under a variety of names including dimethyl sulfone, methyl sulfone, sulfonylbismethane, organic sulfur, or crystalline dimethyl sulfoxide [1]. Prior to being used as a clinical application, MSM primarily served as a high-temperature, polar, aprotic, commercial solvent, as did its parent compound, dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) [2]. Throughout the mid-1950s to 1970s, DMSO was extensively studied for its unique biological properties including its membrane penetrability with and without the co-transport of other agents, its antioxidant capabilities, its anti-inflammatory effects, its anticholinesterase activity, and its ability to induce histamine release from mast cells [3]. After Williams and colleagues [4,5] studied the metabolism of DMSO in rabbits, others postulated that some of the biological effects attributed to DMSO may in part be caused by its metabolites [6].

In the late 1970s, Crown Zellerbach Corporation chemists, Dr. Robert Herschler and Dr. Stanley Jacob of the Oregon Health and Science University, began experimenting with the odorless MSM in search of similar therapeutic uses to DMSO [7]. In 1981 Dr. Herschler was granted a United States utility patent for the use of MSM to smooth and soften skin, to strengthen nails, or as a blood diluent [8]. In addition to the applications laid out in the first Herschler patent, subsequent Herschler patents claimed MSM to relieve stress, relieve pain, treat parasitic infections, increase energy, boost metabolism, enhance circulation, and improve wound healing [9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16], though there is little supporting scientific evidence [17]. On the other hand, the scientific literature does suggest that MSM may have clinical applications for arthritis [18,19,20] and other inflammatory disorders such as interstitial cystitis [21], allergic rhinitis [22,23], and acute exercise-induced inflammation [24].

Although MSM research has expanded since the patents of Herschler and one MSM product (OptiMSM®; Bergstrom Nutrition, Vancouver, WA, USA) was granted the Generally Recognized As Safe (GRAS) status by the Food and Drug Administration in 2007 [25], the use of MSM remained largely unchanged from 2002 to 2012 [26]. For example, according to the 1999–2004 National Health and Nutritional Examination Survey (NHANES), the weighted percentage of regular MSM users was 1.2% [27]. A 2007 study using a subjective survey reported that 9.6% of survey completers had tried MSM [28]; however, the sample of those who completed the survey was not diverse. More recent analysis of past data from the National Health Interview Surveys (NHIS) asserts that MSM use had dropped 0.2 percent points between 2007 and 2012 [26]. In more recent years, it appears that MSM use is on the rise, based on current MSM sales data.

1.1. MSM Synthesis—The Sulfur Cycle

MSM is a member of the methyl-S-methane compounds within the Earth’s sulfur cycle. Natural synthesis of MSM begins with the uptake of sulfate to produce dimethylsulfoniopropionate (DMSP) by algae, phytoplankton, and other marine microorganisms [29]. DMSP is either cleaved to form dimethyl sulfide (DMS) or undergoes demethiolation resulting in methanethiol, which can then be converted to DMS [30]. Approximately 1%–2% of the DMS produced in the oceans is aerosolized [29].

Atmospheric DMS is oxidized by ozone, UV irradiation, nitrate (NO3), or hydroxyl radical (OH) to form DMSO or sulfur dioxide [30,31,32,33,34,35]. Atmospheric levels of DMSO and MSM appear to be dependent upon the season with a maxima in the spring/summer and minima in the winter [36], possibly due to DMS production and volatility being temperature dependent. Oxidized DMS products like sulfur dioxide contribute to increased condensation and cloud formation [37,38], thus providing a vehicle for DMSO to return to Earth dissolved in precipitation where it can undergo disproportionation to either DMS or MSM [39].

Once absorbed into the soil, DMSO and MSM will be taken up by plants [40] or utilized by mutualistic soil bacterium such as the bioremediative additive, Pseudomonas putida, in order to improve soil conditions [41,42,43,44,45,46]. MSM is broadly expressed in a number of fruit [40,47], vegetable [40,47,48], and grain crops [47,49], though the extent of MSM bioaccumulation is dependent upon the plant. At this point, MSM and the other sulfur sources are consumed as a plant product and excreted, released as a by-product of plant respiration in the form of sulfide, or eventually decompose as the plant dies. The non-aerosolized sulfur sources can then be oxidized to sulfate and incorporated into minerals, which undergo erosion and return to the oceans, thus completing this sulfur sub-cycle.

Alternatively, synthetically produced MSM is manufactured through the oxidation of DMSO with hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) and purified by either crystallization or distillation. While distillation is more energy intensive, it is recognized as the preferred method [50] and utilized for manufacture of the GRAS OptiMSM® (Bergstrom Nutrition, Vancouver, WA, USA) [25]. Biochemically, this manufactured MSM would have no detectable structural or safety differences from the naturally produced product [51]. Since the concentration of MSM is in the hundredths ppm in food sources, synthetically produced MSM makes it possible to ingest bioactive quantities without having to consume unrealistic amounts of food.

1.2. Absorption and Bioavailability

Exogenous sources of MSM are introduced into the body through supplementation or consumption of foods like fruits [40,47], vegetables [40,47,48], grains [47,49], beer [47], port wine [52], coffee [47], tea [47,53], and cow’s milk [47,54]. Along with MSM, absorbed methionine, methanethiol, DMS, and DMSO can be used by the microbiota to contribute to the MSM aggregate within the mammalian host [55,56,57]. Diet-induced microbiome changes have been shown to affect serum MSM levels in rats [58] and gestating sows [59]. That said, the gut flora is readily manipulated by diet [60], exercise [61], or other factors and likely affects bioavailable MSM sources, as suggested in pregnancy [62].

Pharmacokinetic studies indicate that MSM is rapidly absorbed in rats [63,64] and humans [65], taking 2.1 h and <1 h, respectively. Similar studies utilizing DMSO in monkeys demonstrate rapid conversion of DMSO to MSM within 1–2 h after delivery via oral gavage [66]. Humans ingesting DMSO oxidized approximately 15% to MSM by hepatic microsomes in the presence of NADPH2 and O2 [56].

In rats, between 59% and 79% of MSM is excreted the same day as administration in urine, either unchanged or as another S-containing metabolite [64]. Urine is the most common form of excretion as MSM has been detected in urine of rats [63,67], rabbits [4,5], bobcats [68], cheetahs [69], dogs [70], monkeys [66], and humans [4,62,71,72]. Additionally, excretion of MSM can be contained in feces [63,64] or several other biofluids including cow’s milk [54,73], red deer tail gland secretion [74], and human saliva [75].

The remaining MSM exhibits fairly homogeneous tissue distribution and a biological half-life of approximately 12.2 h in rats [63]. Tissue distribution in humans is also likely widespread as it has been detected in cerebrospinal fluid and evenly distributed between the gray and white matter of the brain [76,77,78,79,80]. Moreover, the biological half-life within the brain is an estimated 7.5 h [79], while the general half-life is suggested to be greater than 12 h [65]. The persisting systemic MSM comprises the bioavailable source.

MSM is a common metabolite with a steady state concentration dependent upon an assortment of individual-specific factors including, but not limited to, genetics [55,67,81] and diet [58,59,82]. In 1987 the first reported baseline MSM levels were 700–1100 ng/mL or 7.44–11.69 µmol/L [83]. Similar results have been observed with levels in the low micromolar range of 0–25 µmol/L [55]. More recently, a possible discrepancy has been noted in a study report listing baseline MSM levels ranging from 13.3 to 103 µM/mL [65]. In a recent human study involving daily ingestion of MSM at 3 g by 20 healthy men for a period of four weeks, it was noted that serum MSM was elevated in all men following ingestion, with a further increase at week 4 versus week 2 in the majority of men [84]. These data indicate that oral MSM is absorbed by healthy adults and accumulates over time with chronic intake.

2. Mechanisms of Actions

Due to its enhanced ability to penetrate membranes and permeate throughout the body, the full mechanistic function of MSM may involve a collection of cell types and is therefore difficult to elucidate. Results from in vitro and in vivo studies suggest that MSM operates at the crosstalk of inflammation and oxidative stress at the transcriptional and subcellular level. Due to the small size of this organosulfur compound, distinguishing between direct and indirect effects is problematic. In the sections to follow, an attempt will be made to describe each mechanism within a focused scope.

2.1. Anti-Inflammation

In vitro studies indicate that MSM inhibits transcriptional activity of nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NF-κB) [85,86] by impeding the translocation into the nucleus while also preventing the degradation of the NF-κB inhibitor [86]. MSM has been shown to alter post-translational modifications including blocking the phosphorylation of the p65 subunit at Serine-536 [87], though it is unclear whether this is a direct or indirect effect. Modifications to subunits such as these contribute heavily to the regulation of the transcriptional activity of NF-κB [88], and thus more details are required to further understand this anti-inflammatory mechanism. Traditionally, the NF-κB pathway is thought of as a pro-inflammatory signaling pathway responsible for the upregulation of genes encoding cytokines, chemokines, and adhesion molecules [89]. The inhibitory effect of MSM on NF-κB results in the downregulation of mRNA for interleukin (IL)-1, IL-6, and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) in vitro [90,91]. As expected, translational expression of these cytokines is also reduced; furthermore, IL-1 and TNF-α are inhibited in a dose-dependent manner [90].

MSM can also diminish the expression of inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) and cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) through suppression of NF-κB; thus lessening the production of vasodilating agents such as nitric oxide (NO) and prostanoids [86]. NO not only modulates vascular tone [92] but also regulates mast cell activation [93]; therefore, MSM may indirectly have an inhibitory role on mast cell mediation of inflammation. With the reduction in cytokines and vasodilating agents, flux and recruitment of immune cells to sites of local inflammation are inhibited.

At the subcellular level, the nucleotide-binding domain, leucine-rich repeat family pyrin domain containing 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome senses cellular stress signals and responds by aiding in the maturation of inflammatory markers [94,95]. MSM negatively affects the expression of the NLRP3 inflammasome by downregulating the NF-κB production of the NLRP3 inflammasome transcript and/or by blocking the activation signal in the form of mitochondrial generated reactive oxygen species (ROS) [90]. The mechanisms by which MSM demonstrates antioxidant properties will be discussed in the following section.

2.2. Antioxidant/Free-Radical Scavenging

Although an excess of ROS can wreak havoc on a number of intracellular components, a threshold amount is required to activate the appropriate pathways in phenotypically normal cells [96]. The antioxidant effect of MSM was first noticed when the neutrophil stimulated production of ROS was suppressed in vitro but unaffected in a cell free system [97]; for that reason, it was proposed that the antioxidant mechanism acts on the mitochondria rather than at the chemical level.

MSM influences the activation of at least four types of transcription factors: NF-κB, signal transducers and activators of transcription (STAT), p53, and nuclear factor (erythroid-derived 2)-like 2 (Nrf2). By mediating these transcription factors, MSM can regulate the balance of ROS and antioxidant enzymes. It is important to note that each of these is also, in part, activated by ROS.

As mentioned previously, MSM can inhibit NF-κB transcriptional activity and thus reduce the expression of enzymes and cytokines involved in ROS production. Downregulation of COX-2 and iNOS reduces the amount of superoxide radical (O2−) and nitric oxide (NO), respectively [86]. Additionally, MSM suppresses the expression of cytokines such as TNF-α [86,90,91], which may reduce any stimulated mitochondrial generated ROS [98]. Decrements in cytokine expression may also be involved in reduced paracrine signaling and activation of other transcription factors and pathways.

MSM has been shown to repress the expression or activities of STAT transcription factors in a number of cancer cell lines in vitro [99,100,101]. The janus kinase (Jak)/STAT pathway is involved in regulation of genes related to apoptosis, differentiation, and proliferation, all of which generate ROS as a necessary signaling component [102,103,104]. Signaling through the Jak/STAT pathway may also be stifled by reduced cytokine expression. Downregulation of the Jak/STAT pathway may further reduce ROS generation by decreasing expression of oxidases [105] and B-cell lymphoma-2 (Bcl-2) [106].

In macrophage-like cells, pre-treatment with MSM in vitro was found to decrease accumulation of the redox sensitive p53 transcription factor [107]. This p53 exhibits dichotomous oxidative function depending on the intracellular ROS levels, whereby, in a general sense, p53 exerts antioxidative functions at low intracellular ROS levels and prooxidative functions at high ROS levels [108]. The antioxidative function of p53 upregulates scavenging enzymes like Sestrin, glutathione peroxidase (GPx) and aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH). The prooxidative function of p53 upregulates oxidases while also suppressing antioxidant genes. For a more in depth summary of p53 and oxidative stress, please see the review by Liu and Xu [108].

Murine neuroblastoma cells cultured with human immunodeficiency virus type 1 transactivating regulatory protein (HIV-1 Tat) displayed reduced nuclear translocation of Nrf2; however, co-culturing with MSM returned Nrf2 translocation to the nucleus to control levels [109]. Nrf2 is well documented for its association with antioxidant enzymes including glutamate-cysteine ligase (GCL), superoxide dismutases (SODs), catalase (CAT), peroxiredoxin (Prdx), GPx, glutathione S-transferase (GST), and others [110]. Though it is unclear what direct effect MSM has on Nrf2, it is worth mentioning that Nrf2 can also be regulated by p53 expression of p21 or Jak/STAT expression of B-cell lymphoma-extra large (Bcl-XL) [111].

2.3. Immune Modulation

Stress can trigger an acute response by the innate immune system and an ensuing adaptive immune response if the stressor is pathogenic. Sulfur containing compounds including MSM play a critical role in supporting the immune response [112,113,114]. Through an integrated mechanism including those mentioned above, MSM modulates the immune response through the crosstalk between oxidative stress and inflammation.